The Jewish community of Den Helder

Names mentioned in the article in order of appearance:

Till the names adoption (1811):

Israel Salomon, Rebecca Salomon

After the names adoption:

Mr. Delaville, Berenstein (Amsterdam, rabbi), Louis Boas(infantry captain), Benedictus Hartog Polak, Mozes Philip Polak, Meijer Mozes Polak, Levie Benoit Moise Polak , Leo Pinkhof (painter), Herman Pinkhof (physician), Adele de Beer (piano teacher), Clara Asscher-Pinkhof (writer), Betty Koekoek, Grunwald family, Caroline Elzas-Grunwald, Rosa Prins.

From the eighteenth century onwards smaller and larger communities started developing in the province of North Holland and Den Helder was a late addition to these. This was the result of new economic perspectives that the fishing village near the Marsdiep was offering.

However, most of the Jews lived in rather poor financial circumstances.

At the end of the eighteenth century Prince William V gave orders to make the Nieuwe Diep harbor near Den Helder suitable as a berth for warships. Laborers from the villages and cities of North Holland were employed for this purpose and as a result also Jewish pedlars came to see if they could earn a living.

Around 1700 there already lived a Jewish businessman in Den Helder. His name appears in connection with a flag incident on March 8th, 1793, the birthday of Prince William V; during the conflict of the Orangists and the Patriots , Israel Salomon and his wife Rebecca Salomon apparently had forced the patriotic postmaster to hang out the Orangist flag. Later, after the Patriots got the upper hand, Israel Salomon had to pay a fine of 50 guilders. In 1799 we again find his name on a list of civil armament as a 54 year old married businessman. The first written documents proving the existence of a Jewish community in Den Helder, made it clear that Jews usually lived in poor circumstances, potentially causing a burden on the town or village concerned. To be allowed to settle in a certain place, it was necessary to have an affidavit from the town from which one originated, promising that this town would be a guarantor in case the person in question had to resort to begging.

Before the establishment of the Batavian Republic in 1795 the Jews belonged to the ‘Jewish Nation’ - they were foreigners. That meant that in places where they received permission to settle they were subject to a so-called ‘Oath for Jewish inhabitants’. Upon departure they had to hand over a declaration to the new city council that they could be held responsible – in case they would become poor in their new place of domicile. Often these declarations (declarations of indemnity) were accompanied by a certificate of good behavior. From such documents it seems that the first Jewish inhabitants of Den Helder were businessmen from Alkmaar and Amsterdam.

After the French period the political situation of the Jews in the Netherlands changed drastically. They had already received equal rights with the Batavian constitution in 1796; in 1816 they belonged to a church council and had complete citizenship. Within the Jewish community, though, there was fear of the loss of Jewish traditions. Twelve main synagogues were established at that time with sub-synagogues in the suburbs and small ones in the outlying districts. In general it was not difficult for Jews to integrate in Den Helder. For some of them even their business went well.

The synagogue

In the beginning a room in someone’s house was used for services. In 1806 there was a proper Jewish community. At that time a building was bought which served as a synagogue. It was a house in the neighborhood of Smid Street and Bree Street, later called Jodensteeg. After two years this building was refurbished as a synagogue.

In 1809 72 Jews lived in Den Helder.

With the fast growth of Den Helder, the Jewish community also became larger (in 1840 there were already 256 Jewish inhabitants) and the synagogue became too small. Apart from the roof being in disrepair, it was thought reasonable to build a new building. Requests for assistance were sent to the Main Synagogue in Amsterdam and a large number of community members promised a weekly contribution. In April 1837 building was started on a piece of land that the municipality of Den Helder had benevolently handed over to the Jewish community. It was situated on Kanaal road, very near Zeedijk. The stone laying ceremony was attended by the Mayor and aldermen. At Rosh Hashana of the same year the inauguration took place. At first, the Jewish community together with guests from other places held midday prayers in the old synagogue in the Jodensteeg and then the four Torah scrolls were brought to the new synagogue in a procession of two kilometers. In front marched the military music corps of the Royal Watch Ship ‘Kenau Hasselaar’, behind them came girls dressed in white, with flower baskets and laurel wreaths, strewing flowers all the way. Behind the girls came four men holding a canopy and the four Torah scrolls. Behind those came 12 young men, each holding a banner of one of the twelve tribes of Israel. After them came the church council and members of the community, joined by many inhabitants of Den Helder. Following those came several vehicles with ladies and at the end a detachment of the 7th Infantry division. Upon the arrival of the procession at the Town Hall the mayor and aldermen, town councilors and high officers in the land and naval forces also joined in. Also attending were some cantors from other church communities.

In the synagogue the procession was welcomed by a choir. After that the cantor from the community of Hoorn sang several psalms as well as the following song by Mr. Delaville, specially composed for this occasion:

And on the salty wetness he will be affected by Thou might.

Along the coast at the sea, led by our feeling,

In the church along its walls

The proud ocean scours and churns

We see all hands raised to Thou, oh God.

From all ends of the earth Thou hearest the mentioning of Your praise

The voice of the Lord undulates along the wide fields of water.

In the course of the years, however, the synagogue building became dilapidated. During the twenties of the 19th century it was decided to build a new synagogue. For this purpose several collections were held. The stone laying was held on May 2nd, 1928. In August of the same year the building was inaugurated with a big celebration. No one could have surmised that this synagogue would last such a short time.

The school

Until 1806 Jewish schools were independent institutions for religious education. Their aim was to teach Jewish values and standards. Reading and writing the Hebrew language was also taught. After 1817 many changes were affected in tuition in the Netherlands, also among the Jews. All Jewish schools had to be closed. They had to be replaced by religious charity schools which were intended for Jewish children of a lower socio-economic milieu. Well-to-do Jews as well as non-Jewish Dutchmen had to make their own arrangements for teaching their children. The Jewish community of Den Helder also had a school. In 1855 the Jewish charity school in Den Helder was attended by 30 boys and 15 girls. The teacher received a salary of 438 guilders. Apparently the housing of the school was very primitive: it was a basement with hardly any light coming in. In 1859, with the assistance of H.M. the King, the county councilors of North Holland, the municipal management and a member of the Rothschild family tuition could make a new start in a new classroom.

In 1857 a new law was issued, allowing special schools alongside the regular ones, but without subsidies. Under these circumstances Jewish tuition could not be sustained and in due course could not be maintained. Jewish children went to public schools. They nevertheless received religious tuition after school hours and on Sundays. However there was no great interest in this and so it steadily deteriorated.

In Den Helder, on the other hand, it turned out better than expected: ‘Every Sunday morning we went to ‘Jewish school’ for a few hours and from a very young age learned to read Hebrew and all prayers we learned by heart. Our teacher was the gazan, cantor in the synagogue. He usually could not keep any order at all and especially the older boys took advantage of this. In any case, somehow, we learned to read and translate the old Hebrew fluently’.

The cemetery

At first, when the Jews of Den Helder were still a small group, they probably buried their dead in the General Cemetery at the foot of the Grafelijkheid Dunes. In 1824 a plot of land belonging to the Crown was handed over to Jewish community. It was situated at the foothills of the Grafelijkheid Dunes, the east side bordered on the General Cemetery and in the North and West there were farmlands and local farmers. At first, the farmer from whom the land was leased raised problems but the Jews nevertheless started with the outlay. In 1827 the cemetery could be put into use. One of the first persons to be buried was Louis Boas, infantry captain. He died on January 26th, 1827 as a result of an accident on the personnel carrier H.M. Wassenaar, which sank near Texel. His monumental tombstone is still one of the most striking tombstones in the cemetery, even today. This cemetery became too small around the middle of the century and permission was requested to enlarge it. However, this request was turned down. In 1936 a small metaher house was built.

There remain about 200 gravestones in the cemetery; the oldest date from 1827, 1830 and 1840. Some of them show a picture of the utensils of a moheel (a person who circumcises).

Social life: the Chevrot

The chevrot (societies) played a large part in Jewish society life. This was also the case in Den Helder with, ranking first , the society “Gemiloeth Chasodiem”. This institution mainly took care of the of the sick and dying. Members of the Chewre Kadieshe society, had the task of watching over the dying, say prayers (sjeimes), to wash (tahara) and dress the corpses and to arrange the funerals.

Furthermore, Jews were engaged in learning (lernen) – the study of the Tora – in a society called the “Chewre”. In Den Helder this chewre was called ‘Talmud Thora’ and was established in 1860. Prominent members sometimes received the title of ‘chower’. This title was conferred by the chief rabbis to persons who lived according to the rabbinical laws, were magnanimous for special services rendered and for contributing to the welfare of the Jewish Community.

Other societies had as their purpose relaxation and development. The Jewish College ‘Nut en Vermaak’ existed in Den Helder, with the motto ‘Peace and Unity’. It was established in 1855, mainly to enact theatre plays and social education.

There was also the Jewish youth college ‘Unity causes pleasure’ its goal being to rehearse musical pieces, while profits of the performances would be made available to the poor.

It seems, therefore, that there was quite a lot of charity work done. There also was a ladies’ chewer/society which took care of the decoration of the synagogue.

The community management

The Jewish community was managed by parnassim, the elders, also called the manhigim. In general there were ups and downs in this honorary job.It was often coveted but also much maligned.

Also in Den Helder there were internal frictions, mostly about financial matters. Sometimes the assistance of the Mayor had to be called in.

Until 1848 subsidies were given by the municipality to the Jewish community, as well as to communities of other denominations, to enable them to support the less well-to-do in their communities. These regulations were changed in 1848. The community subsidies were stopped and those who had relied on this support were forced to go to work in a municipal work place. For their work they received a fee and a free meal. This resulted in a complaint submitted by the Jewish community, as the Jews could only work four full days, because of the Sabbath, and they could not have the meal because it was not Kosher. The community asked therefore for some reimbursement. There was quite some to-do around this issue, but without any result. The frictions within the community usually had financial reasons, but there was also a certain measure of jealousy among the members, which sometimes led to great unpleasantness.

The Rabbi

The Rabbi in a Jewish community usually also was the Gazan/cantor and the shochet/ritual butcher. This was a difficult job and was usually badly paid. The Rabbi and Gazan was also the representative in all kinds of committees, for which he had not always had the necessary training. In the eighteenth century such a Rabbi received his training from an older Rabbi and religious teacher, who taught him the Thora and Jewish literature such as the Shulchan Aruch (table settings), the sixteenth century summary of Jewish laws. In the nineteenth century the aspiring rabbis attended the Dutch Israelite Seminary, a kind of secondary education. A Rabbi in a small community was a sort of jack-of-all-trades: he visited the sick, consoled mourners, he attended brithot mila (circumcisions), Pidion Haben (release of the first-born), Chatunoth (weddings), funerals; in short he was present wherever there was joy or grief.

Jewish life and some Jewish families

On the whole there never was any question about discrimination or anti-Semitism

in Den Helder. Only during election campaigns there were some gangs who were incited against the Jews. Jewish non-commissioned officers and sailors settled in the naval port. On the H.Ms ‘Salamander’ lived a Jewish warrant-officer together with his family, as head of the crew. When a boy was born on board the ship, circumcision of the little boy took place in the presence of the sailors, the Jewish clerics, and the godfather.

The Jews of Den Helder were mostly tradesmen in textiles, cloths, metal – there were butcher shops, a book shop, a baker, but there also was a physician, teachers and seamen. All of them were citizens of high standing. The peak of the Jewish presence in Den Helder was in the middle of the nineteenth century; in 1869 there were 470 Jewish inhabitants, after that their number diminished.

Around the turn of the 19th century there were only 322 inhabitants left and in 1931 the number had dropped to 196. Hereunder follows a summary of some of the Jewish families.

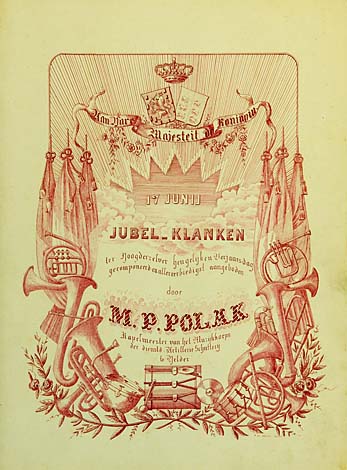

Already in 1801 Heyman Aron Polack settled in this town and after him there followed others bearing the name of Polak. Of those, Benedictus Hartog Polak was known as a dance master. In 1863 it was published in a newspaper that H.M. King William III permitted him to present a booklet in the form of a pamphlet to Prince Alexander of the Netherlands. This booklet was titled ‘something about dancing for youngsters of refined social standing’. For this he received a letter of thanks from His Majesty, as well as a concrete token of his appreciation. In 1868 the Polak family built a grand house in what is nowadays called Koning Street. The house was termed‘the building near the train station’. It was conspicuous because of its size and the large quantity of glass.The Polak family held a modest inaugural ceremony of a religious nature. Several receptions and festivities were held in this building lacking a name, and which only on March 12th, 1869 was named ‘Musis Sacrum’. After the opening of the North Sea Canal the Polak family moved elsewhere, together with the name “Musis Sacrum”. They could now be found in another building on the opposite side of Koning Street. The artistic qualities of the Polak family became apparent during the celebration of the 60 year anniversary of the synagogue; the celebration cantata performed on this occasion was composed by Mozes Philip Polak. The Polak family also opened a banquet hall called the Casino, in which during the course of time all kinds of festivities were held and theater plays performed. The hall became a concept among the citizens in Den Helder. Society life flourished in the Casino. After refurbishing in 1903, the building received a kind of chapel roof with a harp on top which in popular parlance was called the ‘kennel’. The founder, Mozes Philip Polak, was succeeded by his son Meijer Mozes, who left Den Helder in 1939. A sister of Mozes Philip married Benedictus Hartog and together with their sons and daughters they had a dance school in Dijk Street. Another son of Mozes Philip, Levie Benoit Moise Polak had a music shop on Kanaal Way.

Another Jewish person with an artistic streak was the painter Leo Pinkhof. He was born in Amsterdam in 1898 and received his Jewish identity and artistic refinement from his parents, physician Herman Pinkhof and piano teacher Adele de Beer. All their children were intellectually and artistically talented. His sister, Clara Asscher-Pinkhof became well-known as a writer. Leo finished secondary school and went on to study painting at the Royal Academy for Applied Art, at the Rijksmuseum and afterwards he went to the Royal Academy of Visual Arts in Amsterdam. In 1922 he was appointed as teacher in drawing at the artisan school in Den Helder. He was married to the teacher Betty Koekoek of The Hague. They had four children. Leo Pinkhof had very good relations with the Jewish community in Den Helder and he also was co-founder of the local society for artists. In 1940 he was fired by the German occupiers. He then worked as drawing teacher in the workers’ village of Wieringermeer, moved to Amsterdam in 1941, where he still taught, but in the end he and his family were caught, sent to Westerbork and from there to Sobibor.

There were also the Grunwald family members. In the supplement we quote parts of the reminiscences of Caroline Elzas-Grunwald, recalling her childhood in this religious

Jewish family of Den Helder:-(*)

The Jewish labour village (hachshara) in Nieuwesluis in the Wieringermeer Polder

In 1934 various Jewish organizations opened a labour village for young Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria in Nieuwesluis in the Wieringermeer Polder. There, in the middle of newly reclaimed land, the youngsters were taught agriculture and horticulture, cattle breeding and its practice, as well as other professions, carpentry and other technical skills. It was the intention to prepare them for emigration to the erstwhile Palestine. 685 young people attended this labor village, 415 of whom emigrated. Leo Pinkhof of the kehila of Den Helder gave drawing lessons at the village and Rosa Prins taught English. It is not clear whether there was any further contact between Den Helder and the labor village. In 1941 the village was closed by the Germans, the remaining students were arrested and later murdered at Mauthausen. After the war a monument was erected in their memory in Nieuwesluis.

Bombardments

The bombardments in Den Helder in 1940 caused more than 38,000 inhabitants to flee the town, amongst whom many Jews. Those who stayed were first deported to Amsterdam and afterwards via Westerbork to Poland. None of them returned.

(*)-Supplement

“I was born (1913) in Den Helder. My grandfather had left Russia already one and a half centuries ago and had settled in this town. My father had eleven brothers and sisters. Most of them were in business, mainly textiles.

“We lived in the backrooms. Behind the shop there was, after glass sliding doors, a small office in which stood a desk and my mother’s sewing machine with a pedal. Then, through more sliding doors one came into the living room which was rather dark and small. Connected to the living room was a closed veranda with a glass roof – that’s where my father’s bookcase stood, full with beautiful, old books all in Hebrew which he studied every free hour. There were also the dining table and chairs at which we usually ate during weekdays. On Saturdays we ate in the living room. However hard my parents worked, on Friday evenings there came a serene stillness over the house. The men went to synagogue; my mother and I laid the table with a spotless white linen tablecloth with the challot under an embroidered cloth, silver cutlery and china and put food prepared at midday on a tray on top of a small gas flame. This small gas flame had to stay alight until the end of Shabbat in order to keep the food warm. My mother lighted two candles and said a prayer.”

“Oh, that period! I am not idealizing, everything has it’s pro's and cons, every period of time brings with it good and bad things. But during that period one had the opportunity to read, really read. On Saturdays one could not ride a bike, there hardly were any cars, one was seldom confronted with brutality. The whole Friday evening and many hours thereafter, I read. Either that, or I did my ‘verbal’ homework, during the period that I attended Secondary school, because it was forbidden to write.

“A Jewish family lived on Texel and the father came with his son by boat to Den Helder in order to celebrate with us Yom Kippur. My mother had been in the kitchen all day long in order to prepare a wonderful meal as we would have to fast for almost 24 hours – we were also not allowed to drink anything. At the end of the meal there was always tea and a bunch of grapes. That is when, unrelentingly, the time of the fast began. The men went to synagogue, the prayer books and house shoes under their arms, because on the Day of Atonement one was not allowed to go to synagogue in leather shoes. My mother and I quickly still managed to do the dishes, we only had a few minutes left, then we were not allowed to work anymore. Afterwards we also strolled to the synagogue, where there was a very special atmosphere. Many men were dressed in white, and the women looked at their best. In the women’s gallery the women talked softly with each other behind their open prayer books. Sometimes the hum was so loud that the keeper of order had to give an admonishment. When there were three stars in the sky, it was Yom Kippur ‘night’. The next day we spent most of the day in the synagogue. When it was again ‘night’ the women sped home – they were allowed to start making preparations: lay the table, the salted herrings were put into dishes, bread slices were cut and the current breads and challot put on the table, the butter was arranged decoratively and coffee prepared. The smell of the coffee was the most pleasant experience after such a long day of fasting. When the men came home, had put away their clothes and washed their hands, there was an atmosphere of relief and relaxation at the table.

In the course of the week after Yom Kippur a load of burlap bags was delivered at our home, full of accessories and decorations for our Succah – my father and my brothers attached the fir-wood walls with small nails to the wall of the veranda. In between they hung beautiful pictures depicting bible stories. The carpenter came to detach the two middlemost glass roof panels with which the roof was covered and instead arranged a temporary reed mat on it. Over this mat he put a sail which could be pulled outward with a strong cord. So, if it did not rain the sail was rolled up and one could see the sky through the holes of the reed mat, if you sat on the veranda.

“This is how I experienced Judaism during my childhood. In December we celebrated Chanuka, the chanukiot were prepared, my father and my brothers each had one and every evening the candles were lit and we sang the “Maoz Tsur”. Then we all had tea and some sweets and played some games.

In Spring came Purim, when we brought presents to poor people and ate Haman’s ears, thickly covered with powder sugar; in the synagogue we listened to the cantor reading the ‘Megillah’.

“A bit after that came the Pesach festivities. We had a special Pesach dinner set that was only used eight days a year. Our house was cleaned from top to bottom, curtains were washed, rugs were beaten with special verve, walls were re-painted in white – in short the whole house was turned upside down. Food and cookies were only allowed to be eaten on the veranda. Not a single crumb ‘chametz’ (leavened food) was allowed in the rest of the house. The supply cupboard was emptied and thoroughly washed. Rice, pudding powder, semolina and other articles had to be finished before Pesach, otherwise they would be given to the cleaning woman. Everything that was now put in the closet was meant to be used especially for Pesach and had a special Pesach stamp on it. Shopping for Pesach foodstuffs could not be done in Den Helder, but were ordered specially from the greengrocer in the Jodenbree Street in Amsterdam. The wine, that we drank,too,on the first two evenings of Pesach, was ‘casher’, from the firm ‘Carmel’ and this gave us a special sensation as it came from far-away Palestine; the state of Israel did not yet exist. From Enschede came tall, big, round boxes with matzot. The name ‘De Haan’ was baked on each matze, together with little holes. There were ‘eights’ and ‘tens’, which meant that the ‘eights’ were thicker than the ‘tens’. My parents usually ate the ‘tens’ so they felt they had had their fill sooner, and therefore ate less of them. That then didn’t cost extra butter of something else to cover the matzot. On the evening before the Pesach Holiday started, my father and my brothers went, one after the other, through the whole house. My father held in his hand a lit candle and with it, went to look symbolically for chametz. In the evening my mother and I prepared everything for the ‘Seder evening’. On this evening, one of the holiest and fullest of atmosphere of all holidays, the ‘Hagada’ was read.”

This is how most Jewish families in Den Helder celebrated the Holidays.

Source:

Book title: De Kille aan het Marsdiep (1999)

Subtitle: Anderhalve eeuw Joodse gemeenschap in Den Helder.

Author: Joop D.Kila

Publisher: Pirola

ISBN: 9064553165

Extracted from the source:Yael Benlev-de Jong

Translation into English:Nina Mayer

Editing:Ben Noach

Final review:Hanneke Noach

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

The Marsdiep

Den Helder at the beginning of the 20e century