Mozes Goldtsmidt, founder of the Groningen community

by James(Jim) Bennett

(originally an item in the library of the Center for Research on Dutch Jewry, Jerusalem, the print of the Hebrew article was subsequently transferred to the genealogical library of Amoetat Akevoth)

Mozes Goldtsmidt plays a modest role in the history of Dutch Jews, because he is generally only known as the founder of the first, permanent Jewish community in the city of Groningen, even though he lived there only for a short time. However through the discovery of his will in the Amsterdam Municipal Archives[i] and via data from other sources we now know more about him, his family and his life. The many details in his will make his life history more interesting, for without them we would have to rely solely on a dry collection of legal documents.

When the author James Bennett first tried to find out where Mozes Goldtsmidt was born (Hamburg, as we now know from documents in the Netherlands), he was unable to determine who his parents were or even to connect him to any other family in Hamburg towards the end of the 17th century. From a marriage certificate of 29 August 1698[ii] we know however that his father, Joost Goldtsmidt, came from Hamburg. Goldtsmidt’s handwriting in his will was difficult to decipher, so mistakes were made when the document was first copied. In the two places where his Hebrew name appears in full[iii], we understand that it reads: “Mozes the son of community member Jozef Simcha Aharaon Segal or Mozes Simcha Aharon”.

Thanks to the detailed books of the Altona-Hamburg-Wandsbeck communities (known as the A.H.W. communities) most of which remained undamaged, and M. Grunewald’s[iv] thorough book in which nearly all the names on the gravestones in the A.H.W. cemeteries appear, the genealogy of nearly every family who lived in these kehilot at that time can be constructed. Yet it was not possible to identify Josef Goldtsmidt, son of Simcha Aharon, anywhere, and he does not appear in A. Duckes’[v] genealogical research of the Goldtsmidt Oldenburg family either. However mention is made of a Jozef Stadthagen Levi, who like other members of his family, uses two family names: Goldtsmidt and Stadthagen. But he is the son of Mozes Kramer-Goldtsmidt, not of Simcha Aharon. His wife Elkel was a sister of the famous Gluckel from Hamelen[vi]. In his will Mozes Goldtsmidt refers to the seats in the Altona synagoge which used to belong to his uncle “Wolf Fipel”. Assuming this name is another version of “Wolf Finkerle”, who is Gluckel and Elkel’s brother, it can be concluded that Mozes Goldtsmidt from Amsterdam was indeed the son of Jozef and Elkel Stadthagen from Hamburg. It should be noted however that in Duckes’ detailed list in which the names and biographical data of six sons of Jozef and Elker Stadthagen appear (Adel, Hendel, Matte, Freudchen, Benjamin Wolf and Jehoeda Leib), the name Mozes is missing. This poses a problem for the modern researcher. A possible explanation is that Mozes was too young when he left Hamburg for Amsterdam, aged seventeen, to have his presence noted in the documents of Hamburg’s Jewish community, and also the fact there are no lists of births and circumcisions (britoth mila) in the community at that time. Another recently discovered document provides clear proof that Mozes was indeed a son of Jozef Goldtsmidt-Stadhagen. In 1687 the Hamburg community organised a campaign led by Jozef Stadhagen to alleviate the suffering of Ashkenazi Jews in Jerusalem who were oppressed by so-called debts to the Ottoman rulers of the Land of Israel. The compulsory annual payments over many years were recorded in the “donation booklet for the land of Israel 1867-1805” kept by the “synagogue managers of Eretz Yisrael”[vii]. Most community members supported this project, including Gluckel who was a widow at that time. According to this booklet Jozef Stadhagen was the first philanthropist to register and promised to pay twelve Reichsthalers.

His wife Elkele pledged a quarter Reichsthaler every year, while a third pledge was recorded “jointly for her son Mozes and her son Leib, for eighteen Shillings per year for ten years”. This not only proves that Jozef and Elkele had a son called Mozes, but careful examination of the will showed that what at first sight had looked like “Simcha Aharon” because of the difficult handwriting, was in fact “Stadthagen”.

Mozes Goldtsmidt was known during his life time by at least three family names, which was not unusual for Jews in Germany and the Netherlands at the beginning of the seventeenth century. With the legal and commercial authorities in Amsterdam and Groningen his name was recorded in numerous documents under the name of Mozes Goldtsmidt, variously written as Goldtsmidt, Goudsmid and Goldsmid. When he signed himself in Dutch, he used the spelling “Goldtsmidt”. But when, as member of the Jewish community, his name is in Hebrew, he calls himself “Mozes son of Jozef Stadhagen”, as in the last line of his will and on the gravestones of himself and his wife.

Interestingly he was not known as Goldtsmidt or Stadthagen in the kehilla in Amsterdam, but as Cassel after his well-known father-in-law. When his first wife Judith-Gutele died, her name is recorded as “the wife of Mozes Cassel” in the list of deceased, while the text on her gravestone reads “the wife of Mozes Stadthagen Segal[viii]”. Similarly after his own death seventeen years later his name is listed as “Mozes Cassel[ix]” among the deceased and appears as “Mozes son of Jozef Stadthagen Segal” on his gravestone.

Mozes was born in Hamburg in 1681 as the eldest son of Jozef and Elkele Stadthagen’s seven known children. Towards the end of the 17th century his father’s family generally used the name Goldtsmidt. The family was scattered over northern and western Germany (Frankfurt am Main, Hannover, Kassel, Oldenburg, Emden, Halberstadt, Hamburg) and also lived in Amsterdam. His family members were Levites and were described as such in Jewish sources. Marriages were frequently concluded between family members.

Mozes is named after his paternal grandfather Mozes Krammer-Stadthagen who died in 1670, probably in Stadthagen. He is commemorated in the Fulda memorial book as follows:

“The great God-fearing, humble Chassid, chaver Mozes, son of Baruch Daniel Samuel Halevi, may his memory be a blessing, from Stadthagen and his wife the Chassida Gitele, daughter of our teacher Rabbi Meir, may his memory be a blessing, because he voluntarily contributed fifty Reichsthalers to the poor of our city the Holy Community in Fulda. May their souls be bound in the bond of eternal life etc

He died on the Holy Shabbat 9th of Adar tav-lamed (01-03-1670) and was buried on Sunday 10th of Adar (02-03-1670) and she died in the night of the 2nd of Av, when the following day was the second day of Rosh Chodesh in 5429 (29-07-1669) and was buried the same day.[x]

Until his seventeenth year Mozes was a member of the Hamburg community, the life of which is so beautifully described in Gluckel’s memoirs. He was roughly the same age as her sons and absorbed the values and traditions, the family ties and the complicated trade transactions which were typical of Gluckel’s family and of most prominent German Jewish families in that period. Many of the ethical values in Gluckel’s writings are also evident in Mozes’ will, written about twenty years after her memoirs. While Gluckel mentions his sister Elkele only twice briefly, she expresses great admiration for Jozef Stadthagen, her brother-in-law, whom she depended on for business affairs and other advice after the death of her husband Chaim Segal-Hamelen in 1689. Jozef, a prosperous merchant, is described in many documents of the Hamburg community as a founder and leader of devout institutions and many charitable deeds. He donated large sums to the synagogue building and was one of the supporters of the printing of the “Yayin Ja’kov” edition in Amsterdam in 1684. In 1689 he donated 100 Reichsthalers for the foundation of the “shomrim laboker” company (dawn watchers)[xi].

He made business trips to the annual Leipzig fair[xii] and probably to Amsterdam as well, and may have taken Mozes with him for educational purposes. In 1697 or 1698 he arranged the marriage between Mozes and Judith-Gutele, in writing or during of a visit to Amsterdam. She was the eldest daughter of Jehoeda Benjamin Wolf Goldtsmidt-Cassel[xiii] (generally known as Wolf Goldtsmidt), a rich parnas from the Amsterdam community. Wolf was born in Cassel in 1659 and was distantly related to the Goldtsmidt-Stadthagen branch. He arrived in Amsterdam in 1778 and married at the age of nineteen. The marriage initiated by Wolf Goldtsmidt and Jozef Stadthagen was probably the result of long family and commercial relations. Mozes started his commercial career in Amsterdam undoubtedly with financial help from his father, straight after his wedding. He traded apparently in gold and jewellery, as was his father’s main business in Hamburg. He was successful, was involved in many other commercial affairs and had accounts with the Dutch East India Company.

These show that from 1700 to 1704 he sold cotton fabrics for the sum of 10,186 guilders and that his tax bill amounted to 8,347 guilders.[xiv] From 1724 to 1728 the accounts show the continuing sale of coffee, tea, cotton and silk fabrics for a total of 12,121 guilders. He attended the annual Leipzig fair as his father did, for the fair’s registration book shows that Mozes Goldtsmidt from Hamburg attended in the years 1693-1694, 1698, 1700-1703 and 1706-1730[xv]. It is not certain that this was our Mozes, but we know that his father travelled to the annual fair in the years 1675-1679 and 1682-1700, and it is likely that his son joined him on these trips.

After he settled in Amsterdam, he remained a member of the Hamburg community, perhaps to the end of his life and paid tax continuously. According to the community’s tax book Mozes, son of Rabbi Jozef Stadthagen, was assessed for (and paid) 12/531 Reichsthalers in 1704, 466/4 Reichsthalers in 1713 and 626/8 Reichsthalers in 1718[xvi]. After the deaths of his father and his uncle Wolf Finkerle Schtaden (Gluckel’s brother), Mozes inherited their fixed seats, and those of their wives in the women’s gallery in the Hamburg synagogue. In 1718 his name is registered as “Mozes Cassel from Amsterdam”, which showed that his father had died (in 1717 in Amsterdam) and the fact that he added his father-in-law’s name to his own. Mozes and Gutele had eight children, all of whom were born in Amsterdam. The eldest child was Meijer who was born in 1703, and the youngest and last was Fredke-Freudchen who was born in 1718. Three years later disaster struck when Judith-Gutele died aged forty, leaving a grieving husband and eight young children between the ages of three and eighteen. Gutele’s stone in the Muiderberg cemetery[xvii] bears her husband’s moving inscription:

‘There is a dark fence before my eyes when at night, wai-wai, I am troubled by the wailing of Moses, with the weeping of God, because of the death of my serene wife, he took her aged forty Upwards, a woman only dies for her husband, she is Gutele daughter of the notable, leader and governor Wolf Kassel Segal she is the wife of Moshe Stadhagen Segal deceased and buried in good name on Rosh Chodesh Iyar 5481 (28-04-1721).

T N Ts B H”

A year later Mozes married Leonora Reitlingen, the widow of Jacob Meier Enshel from Furth, who lived in Amsterdam with her young daughter Iske (28 May 1722)[xviii]. The couple had no further children. Mozes mentions Leonora in his will in connection with precious stones, jewels, gold and silver which he had given her and which he asks to be returned to his heirs after his death as had been arranged between them and was laid down in the Ketubah in May 1722.

Mozes’ activities in the Amsterdam kehilla have been recorded in the “Memoir Book” of Ozer Leibzoon Ozers, shamash of the Ashkenazi community in Amsterdam from 1716-1731[xix]. Donations from people called up to the Torah on Shabbat and festivals are recorded from 1727 to 1731: Rabbi Mozes Cassel and his sons Meier son of Rabbi Mozes Cassel and Leib son of Rabbi Mozes Cassel gave half a Reichsthaler or guilder at certain times. Some of those donations were presented in honour of Judith-Gittele’s Jahrzeit or for the festivals of Pesach, Shavuoth or Rosh Hashanah. After he had amassed a large fortune and experience in finance Mozes expanded his businesses in 1713.

He had heard that in the city of Groningen – where the settling of Jews had been forbidden for decades – one could gain exclusive rights to a pawnshop. He asked the city council for the right to open a bank and settle there with his family. This was the start of a nineteen-year struggle until the bank was finally opened in 1731 or 1732. In his discussions with the city council, religious and antisemitic objections were aired, and he was questioned on which days the bank would be closed[xx].

On 29 July 1731 the city council decided that a licence to establish a bank would be issued jointly to Mozes Goldtsmidt and a Christian called Jacobus Alders for twenty years, from 1 January 1732 for an annual payment of 1300 Karoli guilders. Goldtsmidt was allowed to bring his family and settle in Groningen, and thus the foundation was laid for the local Jewish community. Goldtsmidt lived in Groningen for about two years, but after the wedding of his daughter Bela-Beletje to Izaak Jozef Cohen in Amsterdam on 26 November 1733, he handed over the reins to Cohen and returned to Amsterdam. In 1736 or 1737 Elkele, another daughter, married Israel Abraham Lazarus Mempel and settled in Groningen. Lazarus joined Cohen in the management of the bank. During that period Goldtsmidt bought houses in Groningen, probably for members of his family. The Jewish community grew slowly and in 1744 it consisted of at least twelve families.

On 23 May 1737 “Mozes Goudsmidt” was the first Jew who was registered in Groningen’s city booklet, which meant that his right to live and trade in the city had been formally approved, something he had already done for five years[xxi]. From 1732 until his death in 1738 he lived in Groningen part of the time, but spent most of his time in Amsterdam to look after his family, the community and his business affairs.

When Mozes reached the age of fifty, after he had gathered a considerable fortune and real-estate, and fulfilled obligations to his wife, children and his grandson Jozef and other family members, he felt the need to record everything he owned in a will, with instructions about what should be done after his death. After writing a document consisting of fifteen paragraphs, he took this to Jan Ardino, a Christian solicitor in Amsterda, on 13 July 1736 to get his approval in the presence of witnesses and permission that it would be stored in the solicitor’s archive[xxii].

About two years later, on 13 Kislev 1738 (25-11-1738), Mozes Goldtsmidt died unexpectedly by drowning, probably in a canal in Amsterdam, or a river nearby, or in the harbour. We suspect that it was an accident, although cases have been known in Amsterdam of Jews being robbed and thrown into a canal. In the death register of the Amsterdam Ashkenazi community his death was recorded as follows:

On the Tuesday of 13th of Kislev the great teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Mozes Cassel, drowned in the water and was buried accompanied by 14 parnassim among whom Rabbi Feibelman Klioz[xxiii].

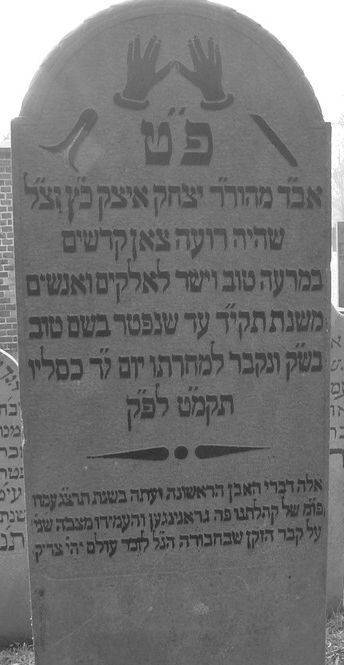

As the title “Our teacher and rabbi Rabbi” is given to rabbis, the question arises whether Goldtsmidt was qualified as such. It is not known that he functioned as rabbi, but it could be that his general knowledge of rabbinical literature entitled him to act as rabbinical judge. In any case the title “Our teacher and rabbi Rabbi” is seldom used, as generally only the title Rabbi is added. Mozes was buried on Muiderberg cemetery the following day. The stone on his grave was inscribed exactly the way Goldtsmidt had determined in his will: Here rests and lies buried Mozes, the son of the community member Jozef Stadthagen Segal, may his soul be bound in the bundle of life. The stone was still there at the beginning of the previous century, and perhaps it is located not far from the stone of his wife Gutele. On 2 December 1738, seven days after his death, Mozes’ will was opened by solicitor Ardino in the presence of six witnesses, among whom his brother-in-law Zecharia Reitlinger and in the absence of his wife and sons, apparently because it was the last day of shiva. The three executors who were appointed by the will, bore both Hebrew names and non-Hebrew names as was customary: Isaschar or Zecharia Reitlinger, Hirsch Halberstadt or Hartog Philip Joost Weber, son of Rabbi Simon Polak or Barend Simons.

The execution of Goldtsmidt’s instructions was a very complicated task, and going by the enormous quantity of legal and notarial documents found in Amsterdam, Groningen and The Hague[xxiv], created serious problems. In 1784 the inheritance affairs were still being discussed in the law courts, and among those involved were Rabbi Shaul Ben Arjeh Leib from Dovna, Amsterdam’s chief rabbi and the community’s parnassim. After Goldtsmidt’s death the management of the bank was transferred from Mozes’ two sons-in-law to his grandson Jozef (named in the will as the son of his long deceased son Mozes), who managed it for fifteen years after which he sold it for 6,220 guilders in 1766[xxv].

Many of Mozes’ descendants lived in Groningen and formed a large group of families connected by marriage, with the names Goldtsmidt, Cohen, Israels and Van Ronkel[xxvi]. His grandson Jozef Goldtsmidt married Kaatje Cohen, a sister of the famous Benjamin Cohen from Amersfoort. Jozef was head of the Jewish community from 1767 to 1784, and his son “Jisraeeltje Cassel” succeeded him and was head for fifty years until his death in 1834. One of Jozef’s eleven sons changed his name from Jechezkieel Cassel to Izikieel Goldtsmidt and was the first Jew to receive permission to study medicine at Groningen University. He obtained his diploma in medicine in 1783. He subsequently excelled as physician in Amsterdam, and in the history of medicine he was pioneer in the inoculation against black pox. From 1814 to 1816 he inoculated 3545 children[xxvii].

Famous among the descendants of Mozes Goldtsmidt was the painter Jozef Israels (1824-1911), the great-grandson of Elkele and her husband Israel Abraham Lazarus. His son Izaak Lazarus Israels (1865-1934) was also a well-known artist.

Another example of the inclination of rich families like the Goldtsmidts to marry other rich and prominent families was the marriage between Batsjewah, Mozes’ daughter, and Tuvia Boaz from The Hague, who was considered by everyone as the richest Jewish Dutchman, with the greatest influence in the second half of the eighteenth century. Both had lost spouses; she was 41 and he was 61. The couple had no children.

It is not my intention to analyse the will in depth and I will confine myself to pointing out a few details to try and explain them and draw a few conclusions. Mozes Goldtsmidt was not a remarkable figure in the history of Dutch Jewry, but his will is a rare document. There are but few such wills from that period and only a few of them have been published as for example the will of Zwi Hirsch, the son of Jacob Kisch from Prague/Groningen which was written in 1799 and published by L. Fuchs in 1969[xxviii].

Some of Mozes Goldtsmidt’s qualities are evident in his will: minute attention to detail, as far as observing religion and financial management are concerned; care for the distant future of his family, even until fifty years after his death; modesty, respect and conscious god-fearing conduct, and an extraordinary generosity towards the poor. Goldtsmidt who knew Hebrew and Yiddish much better than German or Dutch, wrote his will in Hebrew according to Jewish tradition. On the other hand he shows, unusually for Jews, trust in and dependence on non-Jewish officials such Tiadeden, a member of the Groningen city council, in whose hands he puts the care of his possessions, and a few solicitors in whose presence he signed many documents during his lifetime.

As far as his possessions are concerned, Goldtsmidt devotes two entire paragraphs (11 and 12) to the right of inheritance of two seats in the Amsterdam synagogue; Holy Books in his possession he gives to his son and his grandson, while the rest of his estate, including money, jewellery, houses, plots etc. are to be divided between his heirs (paragraphs 7 and 8).

The will shows the pious, comprehensive acquaintance with and knowledge of the sources which can be expected of a learned Jew in his time. He quotes from psalms, Rabbi Ovadja di Bertinora, Rabbi David Kimchi and many pieces from the Torah.

The most interesting part of the will is doubtless Goldtsmidt’s anger at and apparent forgiveness towards his son-in-law Rabbi Izaak Katz, i.e. Izaak Jozef Cohen, the husband of his daughter Bela. In fourteen paragraphs Goldtsmidt issues all kinds of moral and financial commands and out of concern and discretion he does not slander anyone.

However in paragraph fifteen (the last) we suddenly witness something which was without doubt an embarrassing, painful and bad scandal, and which must have been a subject of gossip between Amsterdam Jews at the time. Goldtsmidt writes:

And concerning my son-in-law Rabbi Itsek Katz, the husband of my daughter Bele who kicks against me and has done something which is not done among the people of Israel, who has stolen and been blasphemous and he has broken the oath a few times before my witnesses and G’d and he has broken the law. And he has used his sins and written untruths and lies about me and he has made these up and I protest against the insults he has directed at me. My prayer to G’d is that he will not be punished….

This description is so detailed that the situation is perfectly clear. Together with certain facts which are not included in the will, the following picture emerges: in 1733, a year after the bank in Groningen was established and three years before the drawing up of the will, Mozes’ daughter Bela married Izaak Jozef Cohen, son of a distinguished Hamburg family. As we saw already, Goldtsmidt put him in charge of the bank, while he himself returned to Amsterdam. At some stage Goldtsmidt discovered large differences in the accounts of the bank, and it possibly involved possessions and funds belonging to non-Jewish clients which led to accusations of misuse against Cohen and reciprocal accusations between the two. The conflict was brought before the rabbinical court, probably in Amsterdam, and ended up subsequently at local courts of law, which was against the Jewish tradition and still is. The decision of the Torah and the court accepted Goldtsmidt’s view of events and Cohen scorned the judgements, after he had lied under oath and slandered Goldtsmidt in writing. In the end Goldtsmidt had to pay a lot of money to smooth out the affairs, but the ill feeling and the defamation of the family’s good name and the tense relations in the family certainly were a high price to pay.

With great irony, eighteen years later, after Mozes Goldtsmidt had died and had recovered his good name, Izaak Jozef Cohen was elected as the first rabbi of the Jewish community in Groningen at the age of forty-three. He filled this honourable position for thirty-three years until his death in 1788. It is not known whether he wrote a book, we only know that he wrote an endorsement for an Amsterdam edition of “Mincha Jehoeda” from 1763 by Rabbi Jehoeda, son of Benjamin Wolf Stadhagen from Altona, the son of his wife Bela’s brother.

The inscription on Rabbi Cohen’s stone in Groningen (which is still there in the Jewish cemetery) speaks favourably of course about his long service in the community: “Here is buried Av Beth Din (the head of the Rabbinical court of justice) our Teacher and Rabbi Rabbi Izaak Itsek Ka’tz may the memory of a righteous be a blessing, who was the shepherd of a flock of saints in a good pasture, good and honourable before God and the people from the year 5514 until he died in good name on the Holy Shabbath and was buried the following day the day of 14 Kislev 5549.

These were the words on the first stone: and now in the year 5693 the leaders and governors of our community here in Groningen came and placed a second stone on the grave of the elder of this community, as an eternal memory for a righteous man.”

Translated into Dutch from the Hebrew source:Yael (Lotje) Ben Lev-de Jong

Translated from Dutch: Sara Kirby-Nieweg

Review:Ben Noach

End editing:Sara Kirby-Nieweg & Anthony (Tony) Kirby, Ben Noach

[i] Notarissen archief 1218/9141

[ii] Amsterdams stadsarchief- Puyboek 701, blz.23a in het testament (paragraaf: regel)

[iii] 11:15:3:3 In het testament (paragraaf:regel)

[iv] Max Grunwald, Hamburgs Deutsche Juden, Hamburg 1904

[v] Rabbi Eduard Duckesz, Geschichte des Geschlechts Goldschmidt-Oldenburg, Hamburg 1915, een serie van handschriften van verschillende uitgaven die nooit licht hebben gezien. Ze liggen in de bibliotheek van het instituut Leo Beck, New York: nummer: AR- 318 en in het Centrale Archief van de geschiedenis van het Joodse Volk, Jerusalem.

[vi] De herinneringen van Gluckel zijn uitgegeven in de volgende afleveringen: David Kaufmann, Gluckel von Hameln, die Memoiren der Gluckel von Hameln 1645-1719, Frankfurt a.M. 1896; Bertha Pappenheim, Die Memoiren der Gluckel von Hameln, Wenen 1910; Alfred Feilchenfeld, Denkwurdichkeiten der Gluckel von Hameln, Berlin 1920; Beth-Zion Abrahams, The Life of Gluckel von Hameln 1646-1724, Londen 1962; Marvin Lowenthal, The Memoirs of Gluckel of Hameln, New York 1977; Mira Rafalowitz, De Memoires van Glikl Hameln, Amsterdam 1987

[vii] Het opschrijfboekje bevindt zich in het Centrum van de Geschiedenis van het Joodse Volk, Jeruzalem, nummer 1a AHW.31.

[viii] Het stadsarchief van Amsterdam het dodenboekje van de Ashkenazische gemeente blz. 100

[ix] idem blz. 127

[x] David Kaufmann, Die Memoiren der Gluckel von Hameln. P. XXXIX

[xi] Het Centrale Archief voor het Joodse volk AHW 14 blz. 101

[xii] Max Freudenthal, Leipziger Messgaste, Frankfurt a.d. Main 1928, blz. 124-125

[xiii] Jozef Prijs, Stamboom der familie Goldtsmidt-Cassel te Amsterdam (1650-1750), Bazel 1936, (translation: Jozef Prijs, Pedigree of the family Goldtsmidt-Cassel of Amsterdam (1650-1750), London 1937.

[xiv] Herbert Bloom, The economic activities of the Jews of Amsterdam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Port Washington, New York, London 1969 (reprint of the edition of 1937), Appendix C, pp I,X

[xv] see remark 12.

[xvi] Het stadsarchief van Hamburg, en een afdruk op microfilm in het Centrale Archief van het Centrum van de Geschiedenis van het Joodse Volk, Jeruzalem in het teken HM 8765 blz. 481; HM 8767 blz. 238.

[xvii] De opschriften van honderden grafstenen op de begraafplaats Muiderberg uit de 17e en 18e eeuw zijn in de dertiger jaren geregistreerd door A. Frank. De verzameling bevindt zich in het stadsarchief van Amsterdam.

[xviii] Het Stadsarchief van Amsterdam – Puyboek 713 blz. 88

[xix] De bibliotheek Rosentaliana, Universiteit van Amsterdam Hs.Ros. 266 blz. 22–23

[xx] I. Mendels, De Joodse gemeente te Groningen, Groningen 1910; I.Van Hoorn, De Geschiedenis van de Joden in de Stad en Provincie Groningen, NIW, Nov. 1928 – Aug.1930

[xxi] Het stadsarchief van Groningen: Klein Burgerboek.

[xxii] Zie opmerking 1, hierboven.

[xxiii] Het stadsarchief van Amsterdam, het dodenboekje van de Ashkenazische gemeente, blz. 127

[xxiv] Archief Staten van Holland, Register van Octrooien:1784 (Dubb. Haarlem 68, (fol. 264-268)

Het stadsarchief van Amsterdam: Notaris Pieter Jacobus Scheurleer 10-9-1783

Het stadsarchief van Amsterdam: Rechterlijk Archief nr.1047, f. 136

Het stadsarchief van Amsterdam: Rechterlijk Archief nr. 1049,f. 149

[xxv] Zie opmerking hierboven.

[xxvi] James Bennett. Genealogy of the van Ronkel family of Groningen, Holland and America, Haifa 1985 (MS); James Bennett, Genealogy of the Goldtsmidt-Stadthagen en Goldsmit, Mellrich, Stude, Cohen and Related families of Hamburg-Altona, Cassel and Amsterdam, Haifa 1985 (MS)

[xxvii] Hindle Hes, Jewish Physicians in the Netherlands 1600-1940, Assen 1980, pp. 60-61.

[xxviii] St. Ros, vol. III, no. 2, Amsterdam 1969

|

| Grave stone of Mozes Goldtsmidt at Muiderberg cemetery |

|

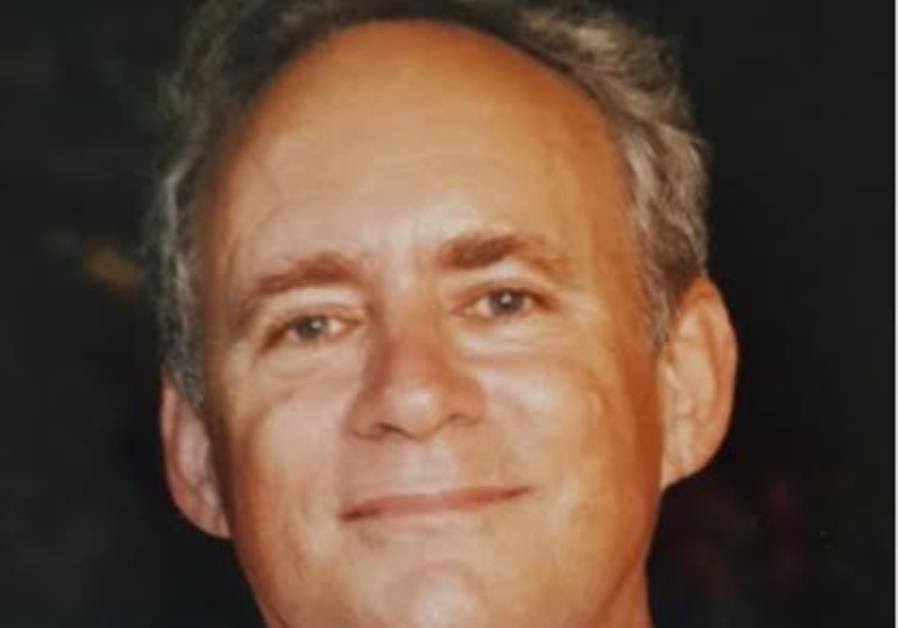

| James Bennett |

|

| Grave stone of Izaak Joseph Cohen in Groningen |