The Jewish community of Harderwijk

(revised and augmented version)

Source:

Joodse Harderwijkers

by Anton Daniels and Nico de Bruijne, with Edward van Voolen.

The middle ages

Already during the Middle Ages Jewish communities or Jewish groups were settled in the duchy of Gelre, especially along the rivers Rhine and IJssel. The duchy of Gelre consisted of four parts: The Veluwe, the Betuwe, the Duchy of Zutphen and Opper-Gelre, with Roermond as capital.

In 1349 the black plague broke out in Europe and the Jews were accused of poisoning the water wells. In Gelre terrible massacres took place by Flaggelants, hordes of religious fanatics. The Jewish communities of Arnhem, Nijmegen, 's Heerenberg, Deventer, Zwolle and Kampen were wiped out.

Harderwijk, a Hanseatic City, was an important trade center, but at the time no Jews lived there, probably because the trade connections of Harderwijk were mainly with northern countries. Most Jews came from the South, mostly from the Rhine region and had their own trade connections.

In the Netherlands the Jews enjoyed a certain measure of protection, since they were money lenders and doctors to princes and nobles and because they played an important role in the growing cities.

However, during the period of Karel V, who ruled from 1519 till 1556, their situation changed. On 20 January 1546 a decree was issued, declaring that all Jews, living in the principality and duchy must leave within one month.

When, in December 1569, the Duke of Alva discovered that one Jew was still living in Zutphen, he immediately ordered this Jew, who was a doctor, to leave the town. Gelre had now become "clean of Jews."

Not all towns forbade the entry of Jews. They made good use of the money paid by the Jews for their residence permit and since the Jews conducted themselves outstandingly, the magistrates were willing to receive them.

The first Jews to arrive in Harderwijk were Spanish Jews, arriving from the Iberian Peninsula, who had been living there as crypto-Catholics from the days of the Inquisition in 1492. They moved mainly to the big towns, like Amsterdam, but also to smaller localities, which encouraged their settling, due to their excellent trade connections.

In the archives we found the name of a Sephardic Jew, Gabriel de Salazar, who was a prosperous man. He married Johanna Mulert Johansdochter, who had been married to an East-Frisian nobleman, Hoyko Manninga tot Pewsum, who had acquired the Staverden estate.

After his death she married Gabriel de Salazar. The couple remained in Staverden. Johanna and Gabriel are mentioned in the town archives, because in 1590 Johanna donated an amount of one thousand daalders to the poor of Harderwijk.

The first mention of a Jew who wanted to settle in Harderwijk dates from 9 November 1657. He had to leave the town every evening, because Jews were not allowed to live there. In this case the rule was not strictly applied. He was supposed to leave town before the first of January 1658, but his expulsion was postponed until the first of May 1658 and then again until September 1658.

The academy

The academy of Harderwijk even admitted Jewish students. Although Jews were not allowed to settle in Harderwijk, several Jewish students studied there. They were mainly young Sephardic students, hailing from Amsterdam. The first Jewish student to finish the Harderwijk academy became a jurist, but he was not allowed to practice his profession. Most Jewish students studied medicine.

In 1711 Abraham de Vries was promoted in Harderwijk. He became a physician to the poor of the Ashkenazi community of Amsterdam. In 1760 Josephus Veersheim studied there and followed in the footsteps of de Vries.

It is noteworthy that in 1683 a Jewish student from Antwerp, Benjamin de Serra, who studied medicine in Harderwijk, was requested to take not only the Hippocratic Oath, but also a second one, where he promised to heal not only his religious brothers, but also Christians. In 1744 a student refused to take the oath bareheaded and his lecturer, J. de Gorter, allowed him to cover his head.

It appears that generally in Harderwijk a relative friendly attitude towards Jews dominated.

One of the lecturers at the Harderwijk academy was professor Joh. Meier, who in 1715 successfully defended several Jews from Nijmegen, who were accused of ritual murder.

On 4 March 1667 the Jewish butcher Jacob Eleaser received a temporary license to open shop in Harderwijk, in order to provide kosher meat to the Jewish students there. It is not known whether he was allowed to settle there permanently.

In 1690 the general attitude of Harderwijk changed to the better regarding residence permits for Jews. In 1706 Jews did not yet receive civil rights, but in 1716 they were entitled to become poorters, which however did not yield the same rights as for citizens.

The Jewish community

The Jewish community of Harderwijk was not founded by the students, who lived in the town for short periods only, and not by individuals like Jacob Eleaser.

The Jewish community was started by Heiman Mozes Heijmans, who, in 1715 founded the loan bank of the town. Till his death in 1742 he remained the managing banker of the loan bank and was followed by Salomon Heijmans, his son.

Jews had to be married according to the general law and not only in accordance with the Jewish custom. The Parnassim were not allowed to receive Jewish guests from out of town, without permission of the mayor.

In 1862 the Jewish community adopted new rules, which divided the community into two groups: immatriculated and not-immatriculated. The members of the first group had paid for their membership and the others of the second group had not. The members of the first group enjoyed several privileges. They could become members of the governing body of the synagogue, and were entitled to receive support in case of poverty. To acquire these rights they paid an amount of 20 till 30 guilders. They had to live a moral life and their marriage had to be arranged according to the Mosaic custom.

Since the election was also bound to prosperity, a small group of governors was formed. The management of the Harderwijk Jewish community was therefore very powerful and ruled from birth to the grave!

Means of living

Like everywhere Jews could not become guild members, but in Harderwijk an exception was made. Membership in the Kramers, or Sint Nicolas guild, the members of which were traders, was open to Jews. The official lotteries were another source of income and the loan bank was usually managed by Jews.

The Loan Bank

The holders of the loan bank were usually the first Jews who received settlement rights. Since Jews were not allowed to become guild members, or holders of official functions, they were usually compelled to become tradesmen.

On 19 September 1715 a charter was given to Heiman Mozes Heijmans to manage the loan bank for a period of twelve years, for which he had to pay the town a yearly amount of 10 guilders and 25 guilders to the hospitals.

From a document dated 30 September 1716, we learn that the presence of Heijmans was valued by the town. The plot behind the Grotepoort was allotted by the town as a Jewish cemetery.

On 5 March 1742 the "Schepenen en Raad" of the town leased the loan bank to the children of Heijmans. When, in 1754, Salomon Heijmans renounced the management of the bank, it was leased to Jacob Marcus & Sons.

In 1771 we read: "Cosman Jacob Marcus, heir to his father Jacobus Marcus, will continue the lease of the loan bank till 1 Mei 1772".

In Augustus 1774 Emanuel, Benjamin and Jacob Meyer Cohen took over the lease for 1/16th part of their profit and in 1846 Mr. Wolf, a Jewish inhabitant of Harderwijk, leased the bank for 332 guilder per year.

The Lottery

For the organization of the "geoctrooieerde stadsloterij", the official town lottery, Jewish cooperation was usually requested, as we can conclude from names like: Moses Godschalk and Ephraim Asser.

Abraham Gabriels, a former money changer from Amsterdam, was a remarkable figure. For a very long time Harderwijk had suffered from the lack of a good harbor. In 1762 Gabriels proposed a plan which would solve the problem. A tontine loan would be arranged which would yield 200.000 guilders for the building of a port.

Since Gabriels, as a former money changer had experience with coins, he discovered at the sale of lots, that some coins were too light in weight. It became clear that fraud had been committed. He discovered the culprit and in 1763 he travelled to The Hague, to meet the essayeur-general of the United Netherlands. The culprit was the corrupt mint master C.C. Novisadi, who enjoyed political backing and finally it was Gabriels who was incarcerated in Elburg! The inhabitants of Harderwijk protested and succeeded in freeing Gabriels from prison. Novisadi was punished, but Gabriels, who did receive a small compensation for his expenses, never received the recognition due to him. From "burger Gabriels" he became "Jode Gabriels" again.

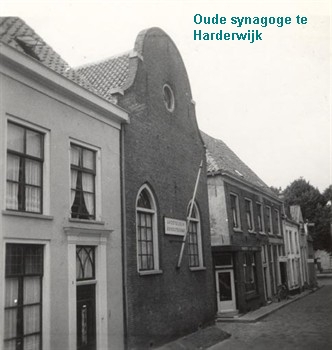

The synagogue

As opposed to towns like Arnhem, Wageningen, Zwolle, Amersfoort and Nijkerk, which already had a Jewish community for many years, Harderwijk was a latecomer on this point. The community there was founded in 1759 only. Their community was small and of little importance. This was strange for a town with such good land and sea connections, which moreover, also had an academy.

Heiman Mozes Heijmans played an important role in the founding of the Jewish community of Harderwijk. He possibly fulfilled his religious duties at home, probably even in secret. When Heiman Mozes Heijmans passed away, his son Salomon continued the Jewish family tradition.

In 1759 the schepenen en raad authorized Salomon Heijmans and Baarend Marcus, to hold prayers in a room hired from Marten Vermeer, which became a home synagogue.

We do not know whether there was a minyan but at the time there was more tolerance, which enabled the Jewish community to act more freely.

In 1814 the house near the home synagogue was bought with financial assistance from Hartog Wolf. Both houses were demolished in 1839, and on the old foundations a new stone synagogue was erected, which was festively inaugurated on Shabbat 7 June 1840.

The alley, were both houses stood, was called de "Jodenkerk steeg". The first stone there is a reminder of the reconstruction. The main synagogue was in Nijmegen, with ring synagogues and minor synagogues in towns around.

According to a royal decree from 1821, the synagogue of Harderwijk belonged to the ring synagogue of Elburg. This synagogue remained in use till the Second World War.

During the war, after the Jews were deported or hidden, their homes were entirely emptied, by order of the Germans. Their furniture and all household effects were taken away by the Dienst Gemeentewerken of the municipality, and were transported by horse and carriage to the synagogue. Really everything disappeared.

In order to make place for all those goods, the interior of the synagogue was demolished. Nothing has been saved.

Finally the synagogue proved too small and later on all household effects were transported to the Klooster at the Kloosterplein.

From October 1943 a guard was hired for 75 cent per hour, in order to guard the Jewish goods. Whether the remaining interior of the synagogue was also brought to the Klooster is unknown.

After the war the ownership of the synagogue and the cemetery were returned to the Jewish community of Harderwijk.

The mikwe

In the year 1762 two mikwa'ot are mentioned, situated in different places of the town. The exact location is unknown, but we know that two mikwa'ot were found under the home synagogue. On 10 september 1976 the Rijksdienst voor Monumentenzorg requested the city council to consider a possible rebuilding of the former synagogue.

In a letter from 11 June 1980, from the Dienst Gemeentewerken addressed to the mayor and aldermen, the following remark is found: "… in accordance with the explicit wishes of the Rijksdienst the mikwe (the bath) shall also be restored."

In spite of this request, the restoration has never been effected and the municipality of Harderwijk has taken no further action. The remainders of the mikwa'ot may still exist under the present synagogue. Their exact location is not clear, since they have been covered by a tiled floor.

The Joodse School (Jewish education)

The Jewish children of Harderwijk were taught by their parents or by a teacher at his home. It is unknown when a Jewish classroom was opened in Harderwijk, but it is sure that there was one.

Meester H.J. Monnikendam was their teacher and he also functioned as shochet and hazzan.

In the middle of the 19th century the Jewish school had 25 pupils, from six to fourteen years, who were divided into three classes. In 1857 a new law obliged all children to go to school. From then on the Jewish children received Jewish teaching on Sundays and during the week after school hours.

In 1875 the Jewish community bought a house for their Jewish teacher.

A new mikwe was built, which was used till after the war. Near the teacher's house was the hewre room, where the several associations of Harderwijk held their meetings. This room was also used for Torah and Talmud studies. Later on the "Soekat Shalom" association was founded, which was fused with the existing Torah and Talmud association.

There were the Kawronim, taking care of the ill and the cleansing of the death, and the women association, Chevras Nosjim shel Emmes, which fulfilled similar tasks.

The classroom was rather small, about five by six meters. In it stood a long table with chairs and near the door was a cupboard with Hebrew books and teaching materials. A coal stove heated the room. Jewish lessons were given there, not only to the Harderwijk children, but also to children from the surrounding villages.

The cemetery

In 1764 the Harderwijk community applied to the authorities regarding a plot for a Jewish cemetery. When the Jewish cemetery was officially inaugurated is unknown. The lot was probably leased from the Westervelt family, who were large-scale landowners.

The cemetery was surrounded with fields and bushes and there were a few farms in the surroundings. The Jewish cemetery was called theJoodenkerkhof. This name also appears in one of the documents of the Sandberg-Westerveldt family, dated 1798. In another document, signed by notary Vitringa from Nunspeet, the same term was found.

Based on the present information we may say that not long after the request from 1764 the Jewish cemetery was inaugurated. Most likely this is the same cemetery as exists today. During the 19th century the cemetery was enlarged.

When the heirs of the deceased could not afford a tombstone, they used a wooden headstone, which in the dry sandy soil of Harderwijk could hold for a long time. Near the cemetery was a small farm, with the metaher house.

During the war gunfire caused damage to some of the tombstones. During the war years three burials took place. The last one, in 1943, was illegal. After the war the Harderwijk municipality took care of the cemetery at the Veldkamp.

The French period

In 1796 the French revolution brought égalité, the separation of church and state and in 1811 family names.

A home for soldiers

Harderwijk was a garrison place with many soldiers and barracks. In 1920 the Joodse Militaire Bond was founded, in order to establish special homes for Jewish soldiers, were kosher meals were provided. It was difficult to find a fitting place in Harderwijk for such a home.

Due to the decline of the local Jewish population not many people used the chewre house in the Hoogstraat anymore and in 1922 the first home for Jewish soldiers was established there.

In 1925 it was moved to the Bruggestraat. In 1927, when most of the military were moved to Amersfoort, the home was closed.

Synopsis and summary

The Jewish community of Harderwijk possessed a synagogue, founded in 1840, situated in the Jodenkerksteeg. There was a Jewish cemetery, a ritual bath (a mikve), and a classroom for bible study and religion. Till 1911 there was a hazzan. The hazzan also functioned as the Jewish teacher. Afterwards the community was financially unable to keep a hazzan and the function was fulfilled by young members of the community. Later on Hartog Hartz became hazzan and shochet.

In 1903 an unpleasant situation arose, when Mr. Kempers, the mayor of Harderwijk, decided to hold the city council elections on a Saturday. The sitting city council argued that the Jewish population would be unable to vote on a Saturday.

The mayor replied however that the Jews were guests only. Please note that this happened more than hundred years after the emancipation.

The scandal was reported in the national press and also came to the attention of Dr. A. Kuyper, the Prime Minister. Through the intervention of L. Wagenaar, the chief rabbi of Gelderland, the matter was settled in a simple way. The polling stations were left open to a late hour, and the Jews could vote after the end of the Shabbat.

About 1920 Jewish refugees arrived from Eastern Europe. They were temporarily housed in the so called Belgenkamp.

From the twenty one Jews deported from Harderwijk not one returned. Some families were hidden during the war. Only two families survived. On the wall of the synagogue a plaque was attached in memory of those members of the Jewish community of Harderwijk, who did not survive the war. In 1947 the Jewish community became defunct and the synagogue was sold to the municipality of Harderwijk.

Extracted from sources:Yael Benlev-de Jong & Anton Daniels

Translated from Dutch:Mechel Jamenfeld

Editing:Ben Noach

Final editing:Hanneke Noach

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

The old Synagogue of Harderwijk

Soldiers in Harderwijk. 1925

The Hartog and Beem families