The Jewish community of Maastricht

Sources:

• J.M.Lemmens, Joods leven in Maastricht, a history of the Jewish community from 1250, written at the 150 yearly existence of the synagogue in the city. de stad (1840-1990).

• Internet

• References to the websites of Akevoth and the Stenen Archief.

• Historical research in de Dutch Jewish press regarding the funtion of chief rabbi Landsberg ,by Moshe Mossel, Jeruzalem, on behalf of Akevoth).

Introduction

Amidst the enormous catholic majority of Limburg, the existence of the small Jewish community was not an easy one. The center of Jewish life was in Maastricht. The Jews had to adapt themselves and the Jiddish language had to retreat. Some external signs of Jewish life were discarded, in order to avoid clashes with the Catholic neighbours. Nevertheless the Jews tried to guard their main Jewish identity, but this was a very difficult struggle. There was not much space for other beliefs in the Catholic region; open discrimination was rare in the rather tolerant Netherlands, but hidden discrimination could be found everywhere.

Signs of a Jewish presence in Maastricht were already found in the middle ages. From the year 1250 approximately there existed a Jewish community in Maastricht which was destroyed in 1350 as a result of pogroms and the loss of commercial functions fulfilled by Jewish traders.

Only in 1648, after the "Eighty Years War" with Spain, a small number of Jews returned to Limburg. The town of Maastricht was however closed to them. Sporadically a few Jews returned to the town, but their return caused violent reactions of the burghers of Maastricht. Jews who were able to further the local economy were admitted, but the less fortunate had to live in Eijsden. Only during the French occupation of Limburg in 1794 did the Jews receive lawful rights and the right of free entrance.

Now a new Jewish community could be developed, as a part of the Consistory of Kreveld. During the 19th and 20th century, this community grew and became a flowering entity.

After 1940 the terrible German occupation put an end to this development.

After the war came a new and difficult period of reconstruction; assistance and sympathy came only in the fifties. In 1990 only about one hundred Jews lived in Limburg and only one Jewish community could be formed, which held their prayers in the synagogue of Maastricht, which by then had existed for 150 years.

Maastricht - the oldest Jewish community in the Netherlands (1250 till 1350).

On Jewish life in the Netherlands during this period, there is little information. During approximately two centuries, Jews lived in small numbers in the southern and eastern parts of the Netherlands. The western part of the Netherlands, Zeeland and Holland, had no commercial importance and were not attractive to the Jews.

The earliest written information regarding the formation of a Jewish community is from a document written in Maastricht in 1295, in which the term Jodenstraat – the "Platea Judeorum" is mentioned, called after the synagogue on that spot. This proves that the Jews of Maastricht had already a synagogue before 1300. Maastricht was an important commercial center, located at the river Maas, on the road from Köln to Flanders.

Since all guilds were closed to Jews during the middle ages, the Jews could trade only in used clothes and provide credit at interest.

However, the rise of the non-Jewish Lombards, who handled the main banking business, forced the Jews to deal in small amounts only.

In 1348 the first pest epidemic broke out. Although the illness hardly touched the Netherlands, people became very anxious. They accused their own sins, but also the Jews, who were accused of poisoning the water wells. The Jews were persecuted and in 1370 they were expelled from the region. In 1377 the synagogue there was not used anymore. The Jews moved to Gelderland and to the Gulikse region, to German regions and to Eastern Europe.

During the 14th century almost no Jews were left in Limburg. There is little information about that period. Their religious and cultural life was presumably the same as in other Jewish communities; they preserved their own tradition, and were proud of their own habits and culture.

Testimony of Jewish life was found in four loose pages, written in middle age Hebrew script. These pages were found in books from Maastricht from the 14th century.

The first page served as cover for the "Cijnsboek van de Pitancie van den Biesen." The second page was found in an archive. The

remaining two pages were part of a cover of a fine registry from Maastricht, kept between 1366 till 1374.

It has not been proved that these pages, which are the oldest remainders of Jewish life in the Netherlands of the middle ages, originate from the Jewish community of Maastricht, but it is plausible, since Maastricht was at the time the only town were a Jewish community was formed.

The negative reaction of the town of Maastricht (1650-1794)

As opposed to the Western part of the Netherlands, where already since the 16th century Jewish communities were formed, their presence in Limburg is mentioned only after the revolution.

During the period from 1350 till 1650 there were almost no Jews in Limburg.

The attitude towards Jews differed from region to region. Mainly during the Spanish period, Jews were not allowed to settle in the Northern part of Limburg (Roermond and Venlo), and therefore more Jews resided in the Southern part, in Heerlen and Sittard.

There were two modes of "Jewish policy" in those regions where Jews were welcome: The Rhineland and the States model. The Rhineland still maintained the strict measures of the middle ages. The exchequer regarded them as "milking cows" and especially in the towns it was very hard for the Jews to integrate.

The States model was principally based on tolerance, which was however left to the goodwill of the local authorities.

In Maastricht which was part of the States, no formal rules regarding the position of the Jews existed and tolerance was only sporadically and reluctantly practiced.

The Jews were allowed to settle there, but there were restrictions, which showed that the Jewish presence was not entirely valuated. The town always attempted to restrict their numbers, in order to avoid the development of a Jewish community. These attempts were mainly induced by the guilds.

A disagreement arose between the Portuguese Jews Machado and Pereira - who provided corn and hay to the army – and the town council, and only through the intensive intervention of the "Raad van State" was the matter solved.

Many Jewish associates of these Portuguese Jews, who lived around Maastricht, started trading on their own in coffee, tea, tobacco, textiles and meat.

During the 18th century the guilds started an anti-Jewish campaign. They rendered a protest with the town council against Jewish competition, and most of the Jews had to leave the town. Other strangers were also treated with suspicion. The town council not always backed the demands of the guilds, but some decisions in favor of the Jews, were later on cancelled.

In 1747 Jewish butchers were invited to Maastricht, since problems had arisen with the meat provision. However, when these problems were solved, the Jews were driven out again.

It seems that in 1785 the situation improved somewhat, when the town council permitted the settlement of three Jews and when not much later, in 1792, the settling of six Jews and their families was legalized. Even this diminutive authorization was given after the council had made sure that no harm would be caused to the local shop owners.

These Jews mainly sold lottery tickets for the General Lottery, which was founded in 1796 and which became the precursor of the State Lottery, founded in 1898.

The small Jewish community held their services at a home synagogue. This house, "het Molenijser", at the Markt no. 53, belonged to Benedict Simon and this home synagogue was probably used since 1782.

In the villages around Maastricht the situation of the Jews was less problematic.

The difference between the Staten-Generaal and the Rhineland regions was not characterized by a greater measure of freedom, but mainly by a different attitude to the social problems caused by the Jewish presence. The Rhineland tried to compose rules for Jews and Christians living together in the same society. The Staten-Generaal left this problem to the lower authorities, who sometimes had different attitudes. As a result poor Jews were concentrated in Limburg and the better situated in the Rhineland. For the Jews in the Rhineland it was easier to follow the rules, but in the regions of the Staten-Generaal poor Jews lived in perpetual uncertainty.

Where Jews were admitted, freedom was exclusively a matter of religion, but social, economic, or political freedom, were not tolerated. In the Staten-Generaal region of Liege–Maastricht the situation was not very different.

The new Jewish community of Maastricht (1794-1814)

The French revolution of 1789 and the Enlightenment accelerated the emancipation of the Jews in Limburg. The French were more than willing to spread their political ideals also outside their country. In 1795 a new order was created. The judicial base was radically renewed. The administration was centralized and many privileges of the social and economic life were abolished. These changes influenced the emancipation of the Jews.

With the annexation of the southern part of the Netherlands, on 1 October 1795, the French legislation pertaining to the Jews was formulated. Following the decisions of the French "Assemblée National," the Jews received full rights and from then on they could be nominated to state or town offices and they were free to trade and settle wherever they wished. In Maastricht this meant that all restrictions were abolished, including the denial of the right to settle, and consequently the number of Jews rose quickly.

In 1794 the estimated number of Jewish families in the town was 22. In 1806 their number rose to 203, and in 1808 there were 215. This rise probably caused the community to move the home synagogue to the highest floor of a house at the Kleine Gracht number 3, also owned by Benedict Simon. The register "Naamsaanneming der Joden" ,(Names adopted by Jews), proves that about half of the Jews of Maastricht were born within the present borders, seventeen of them in Maastricht. Fourteen Jews were butchers, ten were traders, six were pedlars and three were day laborers.

The French reign brought not only the emancipation, but also the organization of the Jewish community. Religious freedom was established and the separation of church and state became a fact.

All religious nominations became now equal to the state nomination. In 1808 the "Consistoire Central des Juifs," which centralized the Jewish synagogues of France, was established. The Jewish community of Maastricht became a part of the "consistory" of Krefeld. Although there were more Jews in Maastricht (215) than in Krefeld (160) the "consistory" was settled in Krefeld, probably as a result of the popularity of the chief rabbi there. In the district of Maastricht twelve Jewish communities were united, including Beek, Elslo, Gulpen, Heerlen, Mechelen, Vaals and Valkenburg. The autonomy of the Jewish communities was expressed in the functioning of their own Jewish jurisdiction. The emancipation of the Jews in Maastricht also caused a certain degree of assimilation. More than before, the Jews became inclined to offer their religious identity for the sake of integration in the surrounding society, but they still suffered from the deeply rooted prejudice of the population and consequently of the authorities.

The effect of organizational and administrational changes

In 1796 the Jewish emancipation decree was published, but only during the reign of King Lodewijk Napoleon the emancipation in the Netherlands was realized.

In September 1808 the Upper Consistory was founded, which caused a unification of the Jewish communities of Amsterdam and other "Ashkenazi" communities in the Netherlands. Only in 1810 the Portuguese and Ashkenazi communities were united in a mixed consistory. After the annexation of Kingdom Holland in 1811, this organization was abolished and replaced by the French consistorial system. Only in 1813 the consistories of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Zwolle and Leeuwarden were founded. After the fall of Napoleon, King Willem I of the Netherlands decided to abolish the French organizational form, and so the Jewish communities became independent again.

The more important communities became "main synagogues" and the smaller ones "ring synagogues." Maastricht became a main synagogue and small synagogues like Sittard, Heerlen, Luik and Luxemburg became ring synagogues. Brussels became a main synagogue.

The services in Maastricht were still held in a private house. But there was a "mikve."The parnassim attended to financial matters and took care of the poor.

After the creation of Belgium in 1830, the "Nederlands-Israelitisch" character of the Dutch community became more accentuated. The 294 Jews of the town were pro-Netherlands and the House of Orange. In 1841 a royal decree stated that the communities in Netherlands Limburg would fall under Maastricht.

After endless discussions during the middle of the 19th century, the Maastricht community revised its regulations in 1861. The revision, fashioned after the regulations of the Ashkenazi community of Rotterdam was quickly passed. The new regulations were more detailed than before.

The "madricula" (the register of members), was abolished. The matriculation had always been a source for discord and quarrels. Its use was against the constitution of 1848, and according to chief rabbi Landsberg, it even went against religious rule.

The church board was abolished and was replaced in 1862 by the "kerkeraad" which was chosen for six years. Since the communities had become more independent, the main kerkeraad seldom convened. The conflict between the Ashkenazi and Portuguese communities was solved by the establishment of two different church boards.

Most Jews of Maastricht lived at a low socio-economic level.

The members of the church board usually belonged to the middle class.

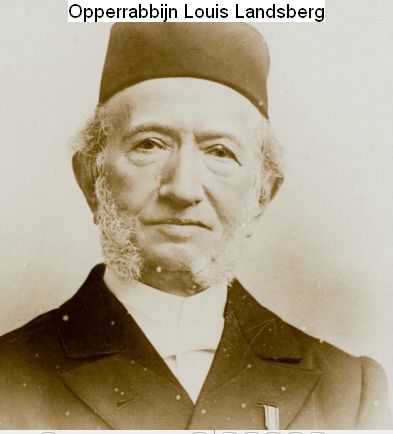

One of the first rabbis in Maastricht, in the new organization of the Jewish communities, was Rabbi Louis Landsberg (1821-1904). Till his death he was a member of the Central Commission of the Jewish Communities in Limburg.

Rabbi Landsberg may be regarded as relatively liberal. In this connection two matters must be mentioned, which drew much attention in the Jewish press and caused a storm of protest.

On "Rosh Hodesh Aw, 15 July 1874, rabbi Landsberg arranged the wedding of lawyer van Raalte from Rotterdam with the daughter of lawyer Ahasverus van Nierop. The wedding took place in the "three weeks," a Jewish religious period of mourning, during which it is forbidden to arrange a marriage. The couple lived moreover in another resort, which was not under the jurisdiction of rabbi Landsberg.

This deed was a blatant violation of the "halacha," the Jewish religious law.

It should be noted that at the time of the wedding of his daughter, lawyer van Nierop was the chairman of the C.C. - the central commission of the Ashkenazi communities in the Netherlands!

Furthermore, in 1869, rabbi Landsberg insinuated against the nomination of rabbi Dunner, who became one of the most important and influential rabbis in the Netherlands.

On 6 November 1964 M.H. Gans published an article in the NIW, on the subject of the verification of the diplomas of Dr. Dunner. Gans proved that rabbi Landsberg and chief rabbi Fraenkel from Overijssel were instigating against the nomination of rabbi Dunner with negative insinuations on this ground.

Another article in the NIW, from 11 April 1874, mentioned that van Nierop, Chairman of the CC, was opposed to the nomination of rabbi Dunner. To his words Van Nierop added a non-flattering citation!

Internal problems and conflicts

One of the main problems of the Jewish community of Maastricht, were members who did not pay their membership fees.

Most of the Jews had settled there after 1815 and at the start they found a community which had not much to offer. There was only a home synagogue, but there was no chief rabbi, and no teacher. Probably there was already a Jewish butcher, without which a Jewish community could not exist. Till 1818 there was no change in this situation. When in 1822 the right to litigate was pronounced, it seemed that these problems could be solved by charging the refusing members, but this solution was not feasible. Nevertheless lawsuits were served, which only caused more conflicts, which were sometimes even fought out in the synagogue.

In March 1825 the parnassim reported on the difficult situation, stating that there was no administration, there were no services and no payments by the community members. By now the debt of the community had risen to 250 guilders and the creditors were "knocking on the doors."

Even within the community problems arose. The butcher did not work in accordance with the Jewish law and was fired, but he did not accept this fact. He also functioned as cantor, but during six weeks he did not appear in "shul."

This chaotic situation continued for many years.

Church Officials (1814-1940)

The Church Officials of a Jewish community defined the community organization. They were the rabbi, the teacher, the person who judged internal conflicts, the cantor, sometimes also functioning as teacher and a "shamash" (the beadle). There also was a kosher butcher and a supervisor ("mashgiah).

In Limburg functioned a chief rabbi, who supervised all local "rabbaniem." The holder of this function had to meet several conditions. He had to be at least thirty years old, married or widower, experienced, holder of certain diplomas, and preferably born in the Netherlands and speaking the Dutch language.

The first chief rabbi of Maastricht was rabbi Glogauer and afterwards there followed a discussion whether the chief rabbi should serve in Maastricht only, or not. The discussion reached one of the ministers of the cabinet and even the King.

Financial problems also played a role, since the Jewish communities of Limburg were not in a good financial condition.

Other chief "rabbaniem." were Schaap, Cohn and Louis Landsberg, already mentioned.

Since many Jews had moved to Western Holland, Louis Wagenaar was now appointed and afterwards officiated Samuel Hirsch the chief rabbi of Overijssel.

Afterwards it was decided that the resorts of North Brabant and Limburg would be united under chief rabbi Heertjes, who continued in this position till after the war, in 1947.

Some famous "mohalim" of Maastricht were Benedict Wesly [see Stenen Archief (209)129] and Salomo(n) Moses Schepp [see Stenen Archief (209)058].

Also compare "Akevoth, The Limburg Circumcision Registers."

These mohalim served an extensive area, including Belgium.

Jewish education

In 1814 King Willem I ordered an inquiry of the educational level at the Jewish schools for the poor. Some communities had Jewish schools and others had only a travelling teacher. The inquiry, completed in 1816, concluded that Jewish schooling showed a lack of civilization and was a form of isolation. The report also noted that only Jiddish was used and no Dutch. Several changes were requested, amongst them the closure of all schools which did not use the Dutch language. Only those teachers who spoke Dutch were allowed to keep their position. Special controlling commissions were established.

Till 1860 Jewish schooling in Maastricht remained not very good. The teachers were not well prepared, and constant rabbinical change and internal conflicts in the community aggravated the situation. Only in 1818 a school commission was appointed, and only in 1833 a Jewish school was opened. The low salary of the teachers was part of these problems.

During the thirties of that century 38 pupils were registered, divided into three classes. Boys and girls were separated.

In 1840 some improvement was felt and near the synagogue a special class room was opened. General lessons were added. But the problems continued and often the teachers had to be changed.

Only in 1857 the situation really improved, thanks to the activities of Samuel Izak van Italie, who succeeded in stabilizing the system. He was active from 1860 till 1904. From then on Jewish teaching in Maastricht remained in good state, till the start of the Second World War.

The synagogue

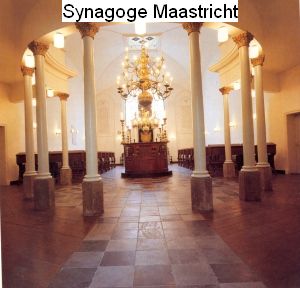

As mentioned before the services were held in a house synagogue and afterwards a location was hired at the Kleine Gracht. In 1818 the parnassim of Maastricht requested authorization to use the inheritage of the deceased rabbi Horwitz for the building of a new synagogue. The authorization was received, but due to financial shortages the building was finished only in 1840.

In 1835 a building fund was opened. The regulations stipulated that donations should be given on a weekly voluntary base, and special donations could be collected from other sources.

In 1838 the parnassim requested authorization to build the synagogue on the plot of the "Kleine Capucijnengang" in the Bogaardenstraat, which request was accepted by the Mayor and the town council. A building plan was made, but it still showed a shortage. The King offered a subsidy of 4900 guilders, for which he received personal thanks from two community members. Even then funds remained short.

Then a collection of "liefdesgiften" - donations of love – was started, donated by the entire Dutch Jewry, which became a great success.

The first stone was laid. The King offered a further subsidy and in 1840 the building was completed! It was insured for 18.000 guilder. The seats were also sold.

The synagogue was erected in a neoclassical style with an interesting architecture. The side wings served as a school room, meeting room, the ritual bath and the home of the beadle.

The inauguration was held during the High Holidays of 1840. All important people of the town, part of them in "grand tenue," took part in the procession from the old synagogue to the new one in the Bogaardenstraat, carrying the Torah rolls.

The Torah rolls were taken seven times around and then placed in the "Aron Hakodesh" the Holy Ark. On Sunday a dinner was hosted, presided by the chief rabbi from Nijmegen,and the festivities were closed with a ball.

In the spirit of the emancipation a choir was founded in order to embellish the church services.

Fitting dress was required, wooden shoes were forbidden, and also the chewing of tobacco. Some of these regulations caused quite a discussion with the smaller Limburg communities. As a result the choir society was temporarily closed. One always tried to preserve the nucleus of Judaism and the parnasim did their utmost to employ a rabbi, a Jewish teacher, a cantor, a beadle and a ritual butcher.

In 1841 the king granted a further subsidy for the decoration of the synagogue. "As an expression of gratitude and thankfulness to our high government" the building commission ordered to coin memorial medals. During the same year King Willem II paid a royal visit to the Jewish community of Maastricht. He was handed a bronze and a silver medal.

In 1865 the synagogue existed 25 years. The jubilee was celebrated by the community. The fifty year jubilee in 1890 was celebrated on a grand scale. The celebration for 100 year could not be held, as a result of the German occupation.

The women societies played an important part in the preparation of these festivities. During the war the Germans caused a lot of damage to the synagogue and all the furniture was stolen. Luckily enough the Torah rolls were saved and all Hebrew books were hidden in the municipal archive.

The copper chandelier and the menorah were also saved.

Only in 1952 could the synagogue be taken into use again and in 1964 a complete restoration was started.

The cemetery

Every Jewish community had a cemetery of its own. Till 1812 Jews were buried at the Maagdendries. Afterwards a Jewish cemetery was used at the Tongerse weg in Wolder, which was part of Oud-Vroenhoven.

In 1842 the cemetery was fenced off ; it was decreed that this eternal place of rest would never be changed. In the cemetery 330 grave stones are found, but possibly there are more graves.

In 1996 the cemetery of Maastricht was cleaned by volunteers. In 2005 a memorial stone was erected for the more than 45 Jewish children from Maastricht who were murdered during the war.

The cemetery at the Tongerse weg bears code nr. 209 in the Stenen Archief, the digitalization project of the Ashkenazi cemeteries in the Netherlands (http://www.stenenarchief.nl).

The grave stones of the before mentioned chief rabbi Juda Horwitz and rabbi Louis Landsberg bear the following codes respectively: (209)001b and (209)091

Societies

Towards the end of the 19th century the Jewish community of Maastricht had the following societies: Care for the poor, a women society, assistance for poor women giving birth, assistance to passing travelers (mainly from Eastern Europe), visiting the ill and the organization of yearly services on dates of death.

Between 1900 and 1940 the town also had a recreation society,

a burial society, and a youth movement. A Zionistic youth movement still existed at the start of the war.

Most Jews were traders, or shop owners. Some were workmen and manufacturers.

The number of Jews in Maastricht and surroundings

|

Year |

Jewish population |

| 1782 | 8 |

| 1794 | 22 |

| 1809 | 209 |

| 1840 | 372 |

| 1869 | 429 |

| 1899 | 405 |

From 1900 and onwards their number decreased. Jews moved to the big towns, as everywhere in the "mediene." In 1930 only 247 Jews were left, but then their number rose as a result of German Jews arriving from Germany.

The fate of the Jews from Maastricht during the Second World War was not different from all Holland. From the 515 Jews in 1940, 120 remained after the war.

After the war

One of the results of the Nazi regime was paradoxically enough, a rise in antisemitism. The returning Jews had to struggle with many difficulties; their possessions were stolen and the Dutch government did not offer any assistance. Only much later the situation was somehow improved. In 1986 the Jewish communities of Heerlen, Maastricht and Roermond were united.

Extracted from source by:Yael (Lotje) Benlev-de Jong

Translated from Dutch by:Michael Jamenfeld

Review:Ben Noach

End editing:Hanneke Noach

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[an error occurred while processing this directive]