The Jewish community of Meppel

Sources:

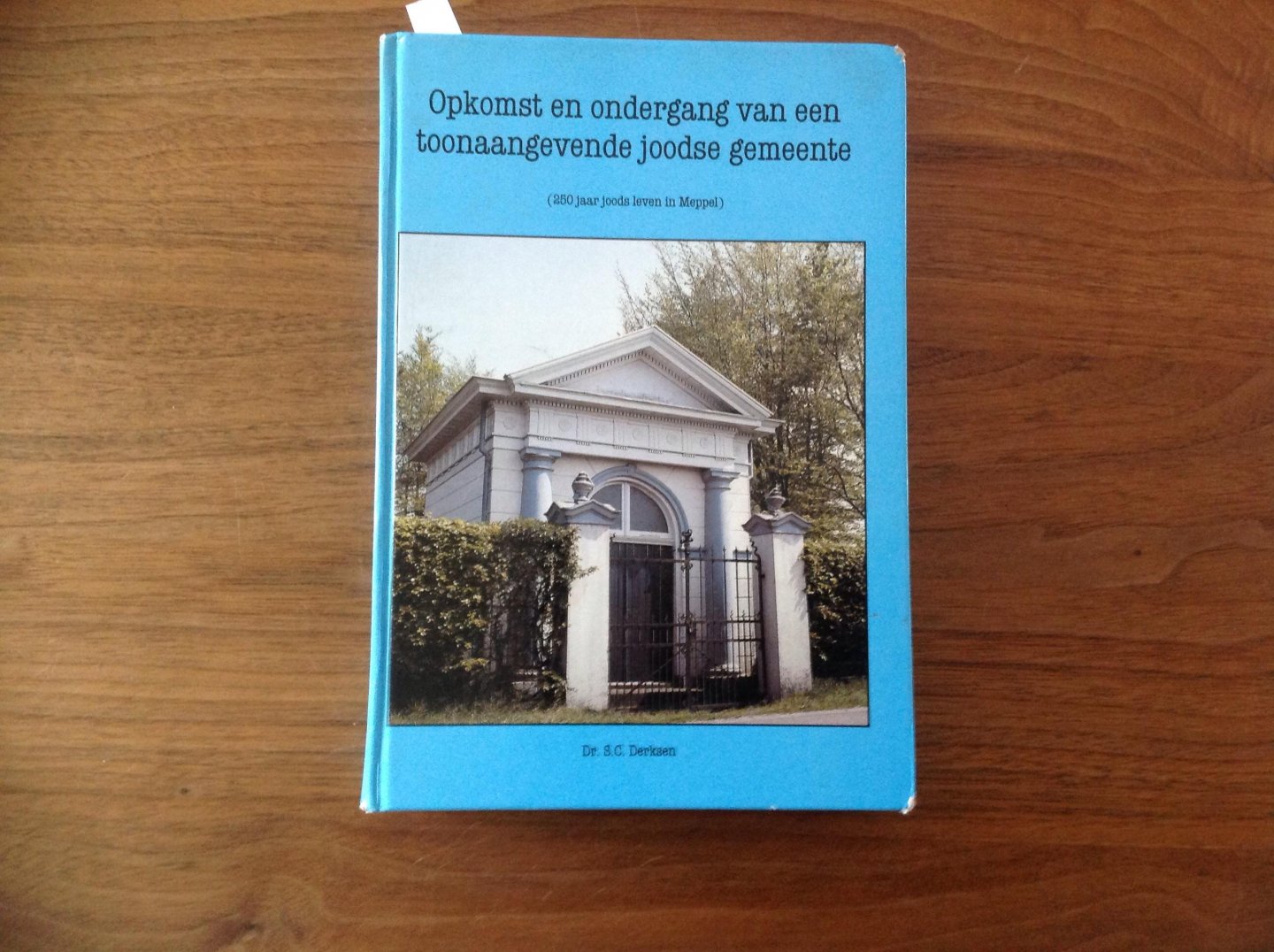

Opkomst en ondergang van een toonaangevende Joodse gemeente (260 jaar Joods leven in Meppel)

ISBN 9789051170405

by Dr. S.C. Derksen

Introduction

Meppel is a city located in the South-West of Drenthe, a province bordering on the province of Overijssel. The Meppel or Meppelt settlement was first mentioned in 1141. Four navigable streams flowed into the river Reest, eventually the Meppeler Diep, which benefited trade with the Western part of the Netherlands. This was certainly the case in the thirteenth century when peat was discovered as a source of fuel. Meppel became a commercial centre, where traders and bargees settled, and peat transport and butter trade formed the basis of Meppel’s economic life.

Culture was also greatly valued in Meppel. There was a Latin school, and the upper classes had liberal ideas, fostering greater tolerance. The small town was predominantly Dutch Reformed. However, after the French period prosperity and population growth declined. From 1848 the situation improved, and Meppel became a commercial centre again. But after 1880 the economic situation deteriorated again which ultimately also affected the Jewish community.

The emergence of the Jewish community in Meppel

It is difficult to determine when exactly the first Jews settled in Meppel. Towards 1300 there were already several fairly prosperous Jewish settlements in the Netherlands, but there was no evidence of a settlement in Meppel. Because of the pest epidemic in Europe in the 14th century, Jews were persecuted horrifically and disappeared from the Netherlands. In the middle of the 17th century the first Jew settled in Meppel. It is always risky to go by names and determine Jewish identity thus. It is not until 1694 that evidence is found of two Jewish couples in the citizen and hearth registers, but a small number of Jews could have lived in Meppel before then as well. It is however generally assumed that Jewish immigration in Drenthe did not start until after 1700, when Meppel attracted many merchants, including Jews, through its trade and inland shipping. Under the citizenship act of 1644 anyone who wanted to settle in Meppel, had to buy citizenship, after which they were entered in the citizens’ register. Thus eighteen Jewish couples bought citizenships between 1729 and 1742. One of the Jews entered was a physician, as ‘Jew doctor’ had been added to his name. Some of them left again, for in the 1742 hearth register only eight Jewish families feature. This is not entirely certain however, as registration was apparently not always carried out meticulously.

Until the compulsory adoption of names in 1812 Jews generally used their fathers’ names as surnames, but this was not always the case. It is now clear that the families with a fixed family name lived continuously in Meppel from the first half of the 18th century to 1942.

There are few direct data about the geographical origin of Meppel’s first Jewish immigrants. Although many came from Poland, Lithuania and Germany, some of them had lived in other parts of the Netherlands previously. A number of these Jewish citizens were well-to-do, but there were also quite a few poor ones among them, who were initially supported by the social welfare service of the Dutch Reformed church. Some of them led a nomadic existence, and some were guilty of criminal behaviour, but information from the Goorspraken (judicial sittings) in Drenthe shows that this was not much of a problem with Jews.

Yet settlement of Jews in 18th century Meppel was restricted. They had to show proof of good conduct when buying citizenship. Generally dignitaries were more sympathetic towards the settlement of Jews than the general public. In 1767 the 12 Jewish families who had settled in Meppel, established a community: the Jewish settlement Jishoeb Meppel became Kehilla Kodesh (Holy Community). That same year regulations were drawn up and a committee was elected, headed by a chairman. Nothing further is known about this, as the records were lost. Their regulations were probably much like regulations elsewhere concerning the position of the church council, the officials (teacher, caretaker and butcher), rental of seats in synagogue, finances, discipline, and care of the poor and the sick. These regulations show the power of the parnassim (governors) and a high degree of self-government. Administration of justice in religious and civil cases rested with the church council. Only in the area of criminal law was the Jewish community not self-governing. Over the years there were several squabbles in the Jewish community for various reasons.

Cemetery

In 1766 a Jewish cemetery was established. Until then the Jewish deceased were buried in the Israelite cemetery in nearby Zwartsluis. A Jewish community had been established there quite early on which kept close ties with Meppel.

In that same year it had been decided to purchase a piece of land in the so-called Boddenkampje. A discussion between nearby neighbours and Meppel’s executive committee meant however that a plot was ultimately bought along the Zomerdijk in Nijeveen which was, like most Jewish cemeteries, located on the district’s edge. The cemetery was surrounded by a wooden fence, later replaced by an iron one. There was also a small metaher house (place for ritual cleansing). This cemetery was, like most Jewish cemeteries, mostly visited in the week before the Jewish New Year, especially by men. Jews with the name Cohen (priest) are forbidden to enter, as cemeteries are considered to be impure. The cemetery measured 2420 square meters. There are now only 354 tombstones left. In Jewish cemeteries there used to be a separation between distinguished members and so-called enrolled members of the community. This depended on the amount members paid the Jewish community.

Synagogue

When the Jewish community in Meppel was originally formed, a home synagogue (i.e. a synagogue in someone’s home) was used for services. In 1767, thanks to a local clergyman, the community was able to occupy a simple house on the Touwstraat (then called Touwbane), next to which the synagogue would be built later. Certain rules had to be observed in the home synagogue, as in the real one later on. Seats had to be rented, and order had to be maintained, and when that was disturbed, fines were handed out, probably also for absenteeism. Services could only be held in the shul, not elsewhere. For the Jewish community the construction of the new synagogue was the most important event in the period 1795 to 1806. The home synagogue, in use until then, had become too small. In 1798 land was obtained, and the first stone was laid that same year. A year later the synagogue was festively inaugurated. Services there were well attended, which meant that especially on the high holidays, but sometimes also during regular Shabbat services, there was not enough space. The land of the Jewish community bordered on the East side of the “Achterom” (Achterumme), from which an alleyway ran to the Touwbaan: the Kernemelksteegje or Jodenkerksteegje (Jewish church alley) as it was sometimes called by the locals. The synagogue which measured 1.8 ares, was situated North of the Jodenkerksteegje. Three houses belonging to the Jewish community were located South of this alleyway, two of which served as a bath house (Mikwe) and warden’s house. The third house was also used for a long time as a meeting room and school. North of this complex a park was created in later years: the Slotplantsoen, where a monument was erected for Meppel’s Jews who had perished in the Holocaust.

Over the years the synagogue became really too small, certainly on high holidays, so when the construction of the school was completed in 1844, a meeting room was used as auxiliary synagogue. This did not solve the problems however, and in 1862 it was decided to convert and enlarge the synagogue on the Touwbaan. Support was requested from among others the Meppeler Courant (Meppel newspaper), and in 1864 the construction contract was put out to tender. The contract for construction and demolition of the garage (used to park the hearse) was given to a builder from Hoogeveen. The hearse was parked in the Grote Akkerstraat, the town’s narrowest property. The stone-laying was carried out by the Chief Rabbi on 13 May 1865 in the presence of many. On 20 October 1865 the synagogue was festively inaugurated. The construction of the synagogue was paid for voluntarily by members of the community, supplemented by a gift from the state treasury and a loan from citizens of all faiths in Meppel.

There were various gifts, such as Jozef Israels’ painting Kerkgang (Churchgoing) and various gifts from Jewish associations. The only item left after the German occupation, was a small silver shield which is now in Herzlia in Israel. Instead of candle light, gas lighting was installed with beautiful chandeliers hanging from the ceiling.

The new synagogue was considerably larger than the old one and could seat 350. It was built in Neo-Romanesque style and had stained-glass windows. As in most synagogues, services were relatively noisy compared with the solemnity of Catholic and Protestant services.

Jewish officials in the community

In general there were the following functionaries: the rabbi, the cantor (chazzan), the teacher, the slaughterer (shochet), the warden (shamash) and the messenger (shaliach).

The rabbi supervises adherence to the Jewish commandments and gives verdicts on matters concerning religious rules. He conducts weddings and divorces, and visits the sick. He only holds sermons on special occasions. Not seldom there existed a tense relationship between the poorly paid rabbi, who had no vote, and the powerful church council; something which also occurred in Meppel more than once. Smaller communities often employed a teacher instead of a rabbi, who was less qualified than a rabbi (who after 1840 was required to have a university degree besides his religious qualification). Meppel had a chief rabbi for many decades.

The cantor led and accompanied the singing in synagogue. Many Jewish communities produced famous singers, as was the case in Meppel. Often the cantor was also required to function as reader and/or teacher. A shochet was needed for kosher slaughtering. The shamash was responsible for announcing decisions, preparing the synagogue for service, opening the Holy Ark and calling up those who could read from the Torah (scrolls of law). The latter was done in Meppel by distributing small metal discs. He also had to read out the psalms which would be sung, and invite people to circumcisions, weddings etc. He often had to function as messenger as well, collecting cash and circulating summonses to meetings. On occasion he was required to announce deaths.

The mohel (circumciser) occupied a special position. It was his responsibility to circumcise little boys. For this he had to be examined by a committee of medical experts, which would include physicians.

Means of existence

Among Meppel’s poor there were also Jews. During the epidemics between 1854 and 1866, and the floods of 1880 and 1890 neglected widows, orphans and the old in particular also needed assistance. Legal provisions did not exist at that time; they did not come into force until the 20th century.

In 1881 the Jewish care relief organisation gave permanent assistance to two Jewish families and three individuals, and temporary relief to five families and seven individuals. In total 38 people needed assistance, while the total number in Meppel for that year amounted to 1262. The number of Jews needing assistance was therefore not very large in those years. This is consistent with the fact that during those years the number of non-paying pupils of the Jewish school in Meppel was proportionally the lowest in the country. In 1878 the total number of pupils in the Jewish school was 65, of whom 8 were non-paying.

Associations

Due to integration and assimilation Jews in Meppel were admitted to non-Christian associations of a general nature. In general it is true to say that Jewish efforts to establish associations unconnected to religious Jewish objectives, were not successful. There were Jewish chairmen of general associations and Jewish participants in several committees, i.e. festival committees, and assistants in committees during the cholera epidemic. One of the organisations which devoted themselves to Jewish charitable causes was Gemilath Gassidim. This organisation had more than 100 members and took care of funerals, care of the poor, medical help etc. In the difficult years of epidemics and floods they were assisted by both the Jewish and non-Jewish population.

Other Jewish associations were Megadleh Jetomim (care of orphans) from 1867, Mishkenot Zakenim (care of the elderly) from 1889, and Sedko Beseser (women’s charitable organisation) from 1886.

There was a loan fund for Jewish merchants. In 1858 there was a youth organisation, which only existed for a short time and about which little is known. In that same year the Maatschappij to Nut van Israel (Association for the Advancement of Israel) was founded, as counterpart to the Maatschappij tot het Nut van het Algemeen (Society for Public Advancement) which did not admit Jews. In 1863 there was also the Broederschap (Brotherhood) society which gave fellow believers financial aid etc. The Israelitische Collectenvereniging, founded in 1867, organised collections for the committee for the poor. The Vereniging tot hulp aan de Wezen (1876) did good work for the 5-6 orphans in Meppel. There were also a few women’s associations and an association for assistance to the elderly. The drama society Door oefening Groter (Improvement through Exercise) was founded in 1894, and in 1896 an association which had to organise a collection of plants for the Feast of Tabernacles, also called centen-chevra, as the weekly contribution was 1 cent.

Education

In general study and education were held in high regard by Jews. Education is regarded as a moral duty in the Torah, and learning (lernen) was important to Jews at home and in shul. Yet during the French occupation Jewish education did not amount to much. Jewish schools for the poor existed only in cities like Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Haarlem and Leeuwarden, which were sometimes subsidised by the city council. In addition there was private education at the homes of the well-to-do, and there were also peripatetic teachers. The Education Act of 1806 specified that education was meant to foster Christian virtues. This isolated the Jews somewhat, although some emancipated Jews did not mind that their children learnt something about Christian values. It was not until 1841 that the first official request was made for the foundation of a Jewish school, which was granted that same year. Shortly after that the construction of the new school in the Touwstraat opposite the synagogue was started. The school was opened the following year. The first floor served as meeting room, and as the shul had become too small in time, also as auxiliary shul.

In a number of places Jewish schools for the poor emerged. They were subsidised by the state or the district. As this was not the case for Christian school, it can be concluded that the special Jewish schools in the Netherlands were the first subsidised schools.

In Meppel not much was known about Jewish education at first, only that a Jewish teacher had been appointed by the Jewish community in 1772. Lessons were very likely in Yiddish and the teacher’s salary was probably paid for by the parents. Round 1810 there were four teachers in Meppel and the construction of a new school was urged. The government was not happy that lessons were in Yiddish, and in 1817 it was decided by Royal Decree that they had to be in Dutch in the future. In 1863 there were 83 Jewish schools with 4155 pupils in the Netherlands, 99 of them (2.4 %) from Meppel. The school in Meppel was qualitatively very good, and one of the best in 1849. In 1857 there was a new education act which determined that the state should no longer subsidise schools run by ‘religious sects’. Jewish children were directed to state schools, which meant that Jewish lessons had to be given after school hours. In 1868 Jewish pupils in Meppel were distributed over various state schools, which meant that the construction of a new Jewish school was no longer an option.

A Kehilla in decline but still prominent

After 1900 the number of Jews in Meppel declined. In 1915 there were fewer than 500 Jews in Meppel. After that this number would gradually drop until it was just over 260 in 1942. The decline in numbers was largely due to the economic situation in Meppel, as was the case generally in the Mediene (the provinces). The number of Jews only increased in the big cities in Western part of the Netherlands. One of the reasons was the collapse of the textile trade because of the emergence of large enterprises in Zwolle and Groningen. Wealthy and enterprising Jewish firms were drawn to the big cities; many were attracted by the higher salaries in the diamond industry in Amsterdam and the pull of academic teaching. The birth rate of the Jewish population had declined, as many of its young people had left and its population was aging. There were more Jews who no longer observed their religion, and more mixed marriages. Thus Meppel’s Jewish population was reduced. After the war there were 27 survivors, some of whom did not come back to Meppel.

Number of Jews in Meppel through the ages

1767 12 families

1791 120

1809 200

1840 390

1869 585

1899 544

1930 304

1951 30

Extracted from source:Yael (Lotje) Ben Lev-de Jong

Translated from Dutch: Sara Kirby-Nieweg

Review:Ben Noach

End editing:Sara Kirby-Nieweg & Anthony (Tony) Kirby

|

| Meppel Synagogue (demolished in 1960) |

|

| Painting of the interior of the Meppel Synagogue by Mark Lisser (at the Monument on Touwstraat) |

|

| The book:"The rise and fall of a leading Jewish Community (200 years of Jewish life in Meppel) by Dr. S.C. Derksen |

|

| The Jodensteeg in Meppel |