The Jewish community of Strijen

Names mentioned in this article (in the order of their appearance):

Before the names adoption:

Simon Izak (van Gelder), Izaak Hartog (van Gelder), Mozes Lichtenstein.

After the names adoption:

Philip Zwarenstein, Gompel Salomon Kleinkramer, Hartog van Tijn, Cornelia Helena (“Truus”) Kleinkramer-Zwarenstein (Teng Teng), Jacob Kleinkramer.

The beginning

The village of Strijen is situated in the Hoekse Waard in the Province of South Holland, on the Northside of the Hollands Diep waterway. In 1759 Strijen was hit by a terrible fire which burnt to ashes three quarters of the village. A document dating from that period shows- for the first time-that Jews lived in Strijen: the house of Abraham Lagerstee was inhabited by a Jew and it remained intact, although it was damaged. The Jew in question was probably Simon Izak, who later called himself Simon Izak van Gelder. He had two children.

In 1777 the above mentioned Simon Izak bought a house at the Doolaartsdijk, which is today called the Boompjes Street. In 1781 he took a second mortgage on the house and its contents. His profession was (Jewish) ritual butcher. His name also appears on the list of able-bodied men which was compiled in 1784 as a result of an outbreak of unrests connected to the demands of the Austrian emperor to permit free passage through the Schelde. At that time Jews did not yet have civil rights – these were granted in 1795 after the French revolution only; they did have civil obligations, though.

During this period it was Izaak Hartog who assumed the name of Van Gelder. The name of Mozes Lichtenstein was also known.

Although Catholics were tolerated the tolerance towards the Jews during that period was amazing. Since the Middle Ages there had been an important immigration of Jews into the Netherlands. They had fled to the West because of persecutions and progroms in Eastern Europe and Germany. In the West they found an atmosphere in which they could live. Economically they had a great influence in these countries. They always helped rebuild the land damaged by water, mainly because of their trading skills.

Jewish immigration into the Netherlands dates from as early on as the Crusades. These refugees were often mistreated – the emperor had the right to keep Jews “as if they were cattle”. He could give them on loan to members of the aristocracy. Because they were not allowed to be members of any guilds, they could only be either tradesmen or street and house cleaners, or butchers.

Documents in Strijen, sometimes one and a half centuries old, attest to the good relations existing between the Jewish butchers, the traders and the local inhabitants. It is difficult to trace further developments during the eighteenth century, but about the nineteenth century more data are known.

Hereunder follow some numbers:

| Year | Jewish population | Total population |

| 1809 | 19 | 2080 |

| 1840 | 35 | 2689 |

| 1869 | 56 | 3833 |

| 1889 | 61 | 4168 |

| 1899 | 50 | 4045 |

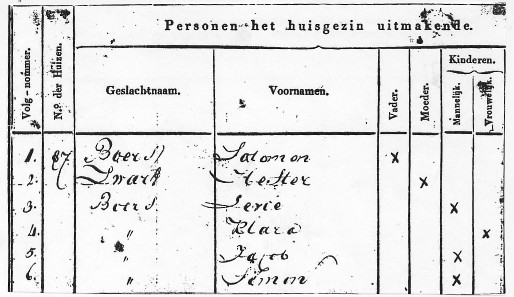

The Imperial Decree of July 20th, 1808 stipulated that all persons, including Jews, had to assume a permanent family name. This order was also followed in Strijen until 1812.

The Jewish community

The synagogue in Oud-Beijerland was called a ring-synagogue. When more than ten male members lived in one place, the synagogue was acknowledged as a separate departmental synagogue. In the beginning of the nineteenth century only in a few places in the Hoekse Waard the Jewish communities possessed more than one house synagogue for services. All places were subordinated to the only proper synagogue at that time in that area – the one in Oud-Beijerland. As from 1857 the Jews of Strijen had an independent Jewish community.

In ‘s Gravendeel there were 12 male members of the community who were regular worshipers, but there was neither a synagogue nor a cemetery. There were also worshipers in Numansorp in 1817, where services were held in the homes of fellow Jews. In order to be recognized as an independent Jewish community one had to pay 40 guilders to the ring-synagogue in Oud-Beijerland. Such a community was recognized in ‘s Gravendeel, but not in Numansdorp as they could not afford to pay the required amount.

In Strijen there was a special place for prayers, but in 1813 it apparently did not exist anymore. In 1852 an attempt was made to acquire a private synagogue but this did not succeed as there were not enough Jews and they were needy, according to their own statements. They did, however, get permission to hold religious meetings in which were recognized as chapels.

The Jews in the Hoeksche Waard belonged to the German-Polish group. They were organized under the (High) German Israelite High Committee in Amsterdam and they belonged to the Rotterdam Section. During the French period registration of the religious communities was initiated. The Dutch-Israelite communities belonging to the Synagogue Section/Authority of Rotterdam in 1862, were the following: Dordrecht, Gouda, Gorinchem, Leerdam, Middelharnis, Oud-Beijerland, Rotterdam, Sliedrecht, Strijen, Schoonhoven and Woerden. Each community was independent. Thus, in the nineteenth century Strijen was one of the many small towns on the South-Holland islands, where an independent Jewish community started to develop.

The Synagogue

Around 1857 Strijen acquired its own synagogue. By that period the Jewish population had grown to more than 50 members. Nevertheless not much can be mentioned with any certainty about the establishment of a synagogue. The population register showed that the building on Kerkstraat 70, as it is known today, was first lived in, afterwards empty and later someone entered ( in a different handwriting) the word ‘synagogue’. The question remains when the Jewish community bought this property. A possible clue could be the memorial stone which had previously been put into the wall near the entrance door; it had two names and the numbers 23. This leads to the question which year is meant. The Jewish year 5623 would fit into the puzzle, namely 1862/1863. This was during the period that this Jewish community flourished most. It is therefore possible that the Jewish community had bought the property, refurbished it and put it into use in 1862.

What did the synagogue in Strijen look like inside? The main entrance was from one side. Near the entrance were four decorative ruby handles. One first entered a lobby where one washed ones hands. From there a staircase led to women’s gallery. Inside the synagogue was a grand chandelier, a bama (pulpit) and an Aron Kodesh in which the Tora Scrolls were kept. There were small benches. The windows were opaque, but they were hardly ever closed. Beneath the lintel was a decorated ledge with the Hebrew text:”How good are your tents, Jacob, your living quarters, o Israel!” (Numbers 24:5). The NSB (Dutch Nazi's) people rebuilt the synagogue during the War. In 1946 the Mol family moved in and in 1973 it was thoroughly refurbished. In the back of the building it is still visible that at once it had another purpose …

Cemetery

In 1894 Philip Zwarenstein and Gompel Salomon Kleinkramer, both members of the Jewish community, requested a permit to build a cemetery.

This cemetery has been in existence since 1895, at the Oude Bonaventurasedijk, at the northerly end of the village. It was also used by the Jews of ‘s Gravendeel and Puttershoek. The first funeral took place in 1896, the last one in 1969. There are in total 23 tombstones, but it is possible that some people were buried without a stone (like the triplets of Hartog van Tijn in 1903). It is also unknown whether persons were buried before the cemetery was officially taken in use. The cemetery is surrounded by ditches with only a narrow little bridge giving access to it, it still radiates an atmosphere of quiet and peace. At the entrance of the cemetery the metaher house still stands – this is the place where the deceased were washed and wrapped into a white sheet, put into a rough wooden box en then buried.

The tombstone of Philip Zwarenstein [(36) 16] distinctly mentiones that he had been a member of the church council and on the stone [(36) 14] of Gompel Salomon is a mention of great value about his task of many years as blower of the Shofar.

The Jewish community in Strijen only had one society – the funeral society Gemieloet Chasadiem.

Jewish School

In 1874 Strijen got a Jewish school in Boompjes street. At the beginning of the twentieth century, in 1908, it was closed and the children from then on attended public school.

Bath House (Mikveh)

Next to the little school was the bath house. During several years after the Jewish school was closed it had still been used by a small group of Jewish women. On Fridays the bath water had to be heated in a big tank (200 liters), and this was not always successful. In 1920 the bath house was also closed.

Livelihood

The Jews of Strijen had several professions. There was, for instance, one Jewish dealer in cattle, one had a drapery shop, and there was one family which sold “Jewish cakes”, quite successfully. There was also a person who repaired watches and a goldsmith who visited his clients with his horse and carriage. Then there was also a shop selling fabrics managed by the four sisters Zwarenstein two of whom were also seamstress and dressmaker. Strijen also had a Jewish piano teacher. There was also a Jewish grocer and kosher butchers.

Philip Zwarenstein was the founder of the sports society ssv Be Quick.

The War

In 1941 there were 18 Jews in Strijen. Of these 15 were deported, twelve perished in Aushwitz, three in Sobibor.

A curious story is the one of ‘Truus Zwarnstein’, or Teng Teng. According to her granddaughter she had never been called Truus. Her official name was Cornelia Helena Kleinkramer-Zwarenstein- Teng Teng.She was born in Indonesia and had an Indonesian mother. With the assistance of a lawyer from Dordrecht she apparently got the name Teng Teng, which protected her from having to wear a Star of David. Her husband, Jacob Kleinkramer, was apparently released from Westerbork because of his mixed marriage, but according to the granddaughter he had never been there, but was in hiding during the whole period in the Biesbosch. Their son had also survived. “Truus” died in 1999.

Source:

Loose pages in a map with the stamp of the Center for Research of Dutch Jewry, Merkaz Dinur.

Titled: "Strijen in historisch perspectief"

No 1 1992 (from the introductory it can be concluded that this a first publication of more to follow).

Uitgave van de oudheidkundige vereniging "Het Land van Strijen".

Extracted from source:Yael (Lotje) Ben Lev-de Jong

Translation into English:Nina Mayer

End editing English:Hanneke Noach

Coordinating of final version:Ben Noach

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

------